July 7, 2021 (EcoSophia.net} -- One of the unexpected benefits of posting my reflections on the future of industrial society in public is that quite often I get advance warning of events on the horizon that others haven’t anticipated yet.

Sometimes, I’m glad to say, it’s because someone in my commentariat happens to have noticed an obscure news story or a little-known fact and brings it to my attention. Fairly often, though, the warning I get has a different and sadder source.

Years ago, a bunch of social psychologists did an ingenious study on the way that the human mind copes with anxiety. They found a river valley with a large and aging dam at its head, and worked their way up the valley, asking people questions about their worries about the dam. Up to a certain point, they got exactly the results you would expect. Far from the dam, where there would be plenty of time for warning sirens to sound and people to get to high ground, anxiety levels were modest; the closer they got to the dam, up to a point, the more anxious people got.

It was when they got so close to the dam that there would be no time to escape the waters that the results spun into intriguing territory. In that part of the valley, and especially where you could see the dam looming up in the distance, people claimed that they weren’t worried at all, and insisted that the dam couldn’t possibly break. Nor could they be swayed from that insistence. The psychologists concluded reasonably enough that the attitude in question was the way that these people dealt with the hard fact that if the dam broke, they had no chance of survival.

It was when they got so close to the dam that there would be no time to escape the waters that the results spun into intriguing territory. In that part of the valley, and especially where you could see the dam looming up in the distance, people claimed that they weren’t worried at all, and insisted that the dam couldn’t possibly break. Nor could they be swayed from that insistence. The psychologists concluded reasonably enough that the attitude in question was the way that these people dealt with the hard fact that if the dam broke, they had no chance of survival.

I found this reaction instantly familiar, because I’d seen the same thing at work in a different context: the history of speculative bubbles. Here the relevant factor is time rather than distance. Those of my readers who watched the rise and fall of the tech stock bubble that burst in 1999 or the real estate bubble that burst in 2008 know that the closer the end comes, and the more obvious it becomes to an impartial observer that prices have lost all touch with reality and the boom will end in a disastrous bust, the more loudly people will insist that it’s not a bubble at all and prices really can keep on soaring to absurd heights forever. It’s not just the brokers and salesflacks who are saying this. Above all, it’s the people who’ve invested their entire net worth in the bubble and face total financial destruction when it pops. They deal with their anxiety by convincing themselves that there’s no way the speculative dam can burst.

It’s a very common human reaction, and it shows up in many other contexts. One of them yields one of the most reliable of the warning signals I mentioned earlier. After more than 16 years of weekly blog posts, I’ve become well known in some corners of the internet for refusing to kowtow to either of the equal and opposite dogmas about the future that hobble our collective imagination these days. I don’t believe in perpetual progress, that is, and I also don’t believe in sudden apocalypse. My take is that our civilization will follow the same long rhythm of rise and fall as every previous civilization; that we have in fact passed our peak and are half a century into decline; that the cascading crises and spreading dysfunctions of our time are equivalents of the crises and dysfunctions that forced all those other civilizations to their knees; and that our decline and fall will unfold in the usual fashion over the next several centuries, in a cascade of disasters interspersed with temporary respites and partial recoveries, ending in a typical dark age half a millennium long from which new cultures will rise in turn.

It’s a very common human reaction, and it shows up in many other contexts. One of them yields one of the most reliable of the warning signals I mentioned earlier. After more than 16 years of weekly blog posts, I’ve become well known in some corners of the internet for refusing to kowtow to either of the equal and opposite dogmas about the future that hobble our collective imagination these days. I don’t believe in perpetual progress, that is, and I also don’t believe in sudden apocalypse. My take is that our civilization will follow the same long rhythm of rise and fall as every previous civilization; that we have in fact passed our peak and are half a century into decline; that the cascading crises and spreading dysfunctions of our time are equivalents of the crises and dysfunctions that forced all those other civilizations to their knees; and that our decline and fall will unfold in the usual fashion over the next several centuries, in a cascade of disasters interspersed with temporary respites and partial recoveries, ending in a typical dark age half a millennium long from which new cultures will rise in turn.

All through those 16 years, I’ve had people showing up on my comment pages to insist that I’m wrong. Pretty reliably, half of them insist that I’m being much too pessimistic and modern technology will surely triumph over all obstacles, and the other half insist that I’m being much too optimistic and modern society will surely be overwhelmed by sudden catastrophe. It’s a source of quite some amusement to me that many of the believers in progress insist that I’m predicting a sudden apocalypse, and many of the believers in apocalypse portray me as a believer in progress. It’s as though they just can’t bring themselves to admit that there’s any alternative to the Hobson’s choice between the two.

The number of people who show up in my comments page and my other points of public contact to make such claims, however, varies quite a bit over time. I’ve noticed, furthermore, that quite reliably I hear from the believers in progress in greater numbers when real trouble is on its way, and I hear from the believers in apocalypse in greater numbers when the crisis du jour has bottomed out and things are beginning to stabilize.

If that indication is anything to go by, dear reader, you may want to brace yourself for rough times, because I’ve recently fielded a flurry of comments insisting that I’m being much too pessimistic and I ought to spend my time talking about rosier futures instead.

I want to talk about one of those comments in particular, which came in response to last week’s post on this blog. It was from a reader named Dani, and the reason I’ve chosen it as a launching point for this week’s post is that it was more thoughtful and interesting than most of the comparable comments I receive. Dani’s point, summed up briefly, was that I practice magic, and therefore I ought to be aware of the power of the human imagination. Why, she asked, am I not helping people direct that power toward envisioning the kind of future that we all want? She challenged me to stop talking about the hard-edged futures that I’ve discussed at length on this blog and instead paint a future inspired by my hopes and dreams.

Her question’s a valid one, but it’s not as rhetorical as Dani seems to think. There are good reasons why I don’t spend my time trying to get people to imagine shining, hopeful futures just now, and those reasons are worth discussing.

“What do you mean, that’s not real science?”Let’s start with some basics. Magic, to cite my favorite definition of the subject, is the art and science of causing change in consciousness in accordance with will. It has nothing to do with special-effects tomfoolery of the Harry Potter variety. (The Harry Potter movies have as much to do with real magic as Young Frankenstein has to do with real science.) Because it works with consciousness, magic has enormous power to shape how we experience the world, and so it can also shape the results we get from our interactions with the world. Success and failure, health and sickness, love and hatred, joy and despair -- all these can be determined by the consciousness with which we encounter our lives, and so all of them can be influenced by magic.

“What do you mean, that’s not real science?”Let’s start with some basics. Magic, to cite my favorite definition of the subject, is the art and science of causing change in consciousness in accordance with will. It has nothing to do with special-effects tomfoolery of the Harry Potter variety. (The Harry Potter movies have as much to do with real magic as Young Frankenstein has to do with real science.) Because it works with consciousness, magic has enormous power to shape how we experience the world, and so it can also shape the results we get from our interactions with the world. Success and failure, health and sickness, love and hatred, joy and despair -- all these can be determined by the consciousness with which we encounter our lives, and so all of them can be influenced by magic.

That does not mean that magic is omnipotent. I had to remind a different reader of that fact a little while back in one of the day-long Ask Me Anything sessions I do for people who are curious about magic. The reader wanted to know if there was any simple magical working I could offer her that would help her get her two-year-old to sit still during dental examinations. My response was that I practice magic; I don’t perform miracles.

That was flippant, of course, but it also tried to make an important point: just because you want something doesn’t mean that magic will do it for you. Causing changes in your consciousness, or that of your two-year-old, will not get the two-year-old to sit still for an hour of physical immobility and acute discomfort in a dentist’s chair, because your two-year-old has good reason to fidget. She’s bored and uncomfortable; unless the dentist is more careful than mine ever was, the exam is going to involve quite a bit of pain; and at the age of two years, very few humans have the neuromuscular coordination and control needed to remain still for an hour at a time, even when they’re not being pinned down and jabbed and hurt.

So magic has limits. The ordinary untrained human imagination -- the instrument Dani wanted me to direct toward the goal of creating a future that we all want -- has even sharper limits. Our current predicament is a good example of this. Countless millions of people over the last couple of centuries have imagined a future of endless technological expansion, unhindered by mere material limits. Their imaginations have been impressively detailed, and gave rise to an entire new genre of literature and visual media, in the form of science fiction. If imagination all by itself was able to elbow its way into reality, we’d be on our way to the stars by now. In the real world, by contrast, human beings haven’t gotten out of near earth orbit since 1973, and those limitless new energy sources imagined so vividly over and over again are still nowhere in sight.

“I’m sorry, your high tech future is permanently out of stock.”The limits of magic can be understood in several ways, which all work out more or less to the same thing. From a materialist perspective, we can say that consciousness can affect physical matter only in certain strictly limited ways. You can do a lot of things by changing the state and contents of your consciousness, in other words, but none of them will make dilithium crystals show up on demand. From the perspective of occult philosophy, by contrast, all things are understood as patterns in consciousness -- what we call matter is simply that set of patterns in consciousness that is most resistant to change -- but the point that sometimes gets missed is that human beings are not the only centers of consciousness that matter.

“I’m sorry, your high tech future is permanently out of stock.”The limits of magic can be understood in several ways, which all work out more or less to the same thing. From a materialist perspective, we can say that consciousness can affect physical matter only in certain strictly limited ways. You can do a lot of things by changing the state and contents of your consciousness, in other words, but none of them will make dilithium crystals show up on demand. From the perspective of occult philosophy, by contrast, all things are understood as patterns in consciousness -- what we call matter is simply that set of patterns in consciousness that is most resistant to change -- but the point that sometimes gets missed is that human beings are not the only centers of consciousness that matter.

In the worldview of occult philosophy, we are still early in the process of spiritual development. Others have gone that way long before us. There are vast centers of consciousness -- call them gods and goddesses if you like -- that create and maintain the conditions that we experience as a material world, and they, not we, decide what those conditions will be. Nor, it probably has to be said, do they display the least interest in changing those conditions just so that our species doesn’t have to face, and learn from, the consequences of its own idiotic decisions. They have watched many other species and civilizations pass through their life cycles before our time, and they will doubtless watch many more go through the same arc long after we’re gone.

That may seem like plain common sense. In some periods of history, however, common sense is far from common, and this is one of them. For the last 300 years, our species has gone its merry way treating the Earth as nothing more than a source of raw materials and a dumping place for our wastes. We plundered the planet’s store of fossil carbon and burnt most of it in a three-century-long orgy of absurd extravagance, and the mere fact that we’ve known for well over 100 years that this was going to end badly didn’t cause more than a very few of us to take up less crazily excessive lifestyles. Now supplies of fossil carbon are running short, the ecological consequences are showing up on schedule, dozens of other hard planetary limits are looming up on all sides -- and of course, this is when people suddenly start saying “Oh, no, this isn’t what we wanted, can’t you come up with some better future for us?”

There’s an even harsher irony here because the benefits of that orgy of consumption have not exactly been shared equally among our species. Right now, the wealthiest 10 percent of humanity is directly or indirectly responsible for 50 percent of all the carbon dioxide being dumped into the atmosphere. (People who love to blame big business for the climate crisis don’t like to talk about the fact that most of what big business is doing with that carbon is producing goods and services, which are disproportionately consumed by the well-to-do.) Nor is it the teeming masses of the poor who are begging me to dream up a better future for them. No, it’s members of the comfortable classes of the industrial world, the same people who’ve benefited most from the joyride, who now want to find some way to avoid getting stuck with the bill.

There are good reasons for me to ignore such requests. Imagine for a moment that you’re in the river valley I talked about toward the beginning of this post, and you happen to pass the dam just in time to see the first stream of muddy water begin to bubble up from a weak spot near its base. You know that this means the dam is going to fail and will give way within hours. You hurry downstream to the nearest town, and somebody looks up and says, “So how’s the dam doing?” Here are your choices: (a) tell them that everything is fine and there’s nothing to worry about, or (b) shout “Grab your family and get out of here, the dam is failing!” Which do you do?

Or let’s say there’s a speculative bubble inflating toward its inevitable crash. You’ve read John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Great Crash 1929, you note that the same slogans deployed to bolster that bubble are being used this time too, and you’re aware that sometime soon it’s all going to come tumbling down. A friend who’s invested some money into the bubble calls you up and asks for your opinion about the state of the market. Here are your choices: (a) reassure your friend that the market can keep going up forever, or (b) explain about speculative bubbles and urge your friend to get every cent out of the market as soon as possible. Which do you do?

In both cases option (a) offers a future that the listeners want, a future strongly appealing to hopes and dreams. In the first case, the people who live below the dam want to believe that the dam is safe and they’ll be able to stay in their homes in comfort and safety; in the second, your friend and the millions of others who’ve invested in the bubble want to believe that they really can get rich by riding the market upward. In both cases, equally, option (b) offers the listeners a depressing prospect in which hopes and dreams have very little place. If hopes and dreams are what matters most, shouldn’t you say the reassuring thing in both cases -- maybe coming up with some vivid, imaginative way of claiming that all the water behind the dam will vanish harmlessly instead of crashing down on the houses and people below, or inventing some equally visionary scenario in which speculative bubbles really can inflate forever?

The problem with this attitude, of course, is that if the dam is breaking or the speculative bubble is already in full spate, there really is no question about what’s going to happen. In one sense or another, a lot of people are going to end up underwater in a hurry, and their hopes and dreams are going to be washed away. In both cases the unwanted consequences of past actions have piled up to the point that crisis is imminent, and the only hopes and dreams that matter are those that might just possible shake people awake and get them to flee out of the valley or cash out of the market before disaster strikes.

It’s a long, slow process.Now of course it’s true that we’re not looking at a single disaster like a dam breaking or a market crashing. We’re looking at the decline and fall of a civilization, a process that has already been under way for half a century and will take centuries more to finish. The same principle applies, however, in at least two ways. First of all, there are plenty of things that can still be done here and now to cushion the process of decline and see to it that as much as possible of the best achievements of our civilization are handed on to the cultures that will build on our ruins. Those things will not be done by people who are still fixated on hopes and dreams of perpetual progress toward a utopian future. (Nor, by the way, will they be done by people who have embraced the belief in instant apocalypse, which is simply another way of evading responsibility for the future.) They will be done, if they are done at all, by those who have shaken themselves free of those delusions, grappled with the harsh reality of our predicament, and aimed their imaginations toward envisioning the best available options in a troubled time.

It’s a long, slow process.Now of course it’s true that we’re not looking at a single disaster like a dam breaking or a market crashing. We’re looking at the decline and fall of a civilization, a process that has already been under way for half a century and will take centuries more to finish. The same principle applies, however, in at least two ways. First of all, there are plenty of things that can still be done here and now to cushion the process of decline and see to it that as much as possible of the best achievements of our civilization are handed on to the cultures that will build on our ruins. Those things will not be done by people who are still fixated on hopes and dreams of perpetual progress toward a utopian future. (Nor, by the way, will they be done by people who have embraced the belief in instant apocalypse, which is simply another way of evading responsibility for the future.) They will be done, if they are done at all, by those who have shaken themselves free of those delusions, grappled with the harsh reality of our predicament, and aimed their imaginations toward envisioning the best available options in a troubled time.

Second, the process I’ve termed the Long Descent stretches out over centuries but its slope is not smooth. In every previons example of the decline and fall of a civilization, there have been periods of crisis interspersed with periods of stabilization and partial recovery, and there’s every reason to think that we’re facing exactly the same thing this time around, too.Some of those periods of crisis in the past have been pretty extreme, furthermore, and here again, there’s no reason to think our case will be any kind of exception.

With that in mind, it’s worth pointing to two crises building here in the United States. The one everyone is talking about these days is the extreme weather in the western half of the country: yet another recordbreaking drought, this time amplified with stunningly high temperatures along the west coast. Those of my readers who know paleoclimatology will be nodding; the rest of you might want to pick up a copy of E.C. Pielou’s classic work After the Ice Age and turn to the section on the Hypsithermal, the period of high temperatures that followed the end of the last ice age. When the global climate is warmer than it’s been in historic times, you see, the desert belt that keeps northern Mexico and the American Southwest dry as dust shifts northward, so that the western Great Plains and the intermountain West all the way north into Canada turns into desert.

Nebraska looked like this in 7000 BC.Thus there’s every reason to expect that the steady drumbeat of heat, drought, and fire that has been hammering the west will pick up the pace year after year, until large sections of the mountain west and the western Great Plains no longer have the water or the climate to support agriculture or, for that matter, human settlements. Over the decades ahead, millions of people will have to find new homes, trillions of dollars of real estate and infrastructure will become worthless, and the consequences of those shifts will shake our economy the way a dog shakes a rat. Though those don’t mean the end of the world, they do mean that a lot of hopes and dreams are burning and there isn’t enough water left in the reservoir to put out the flames.

Nebraska looked like this in 7000 BC.Thus there’s every reason to expect that the steady drumbeat of heat, drought, and fire that has been hammering the west will pick up the pace year after year, until large sections of the mountain west and the western Great Plains no longer have the water or the climate to support agriculture or, for that matter, human settlements. Over the decades ahead, millions of people will have to find new homes, trillions of dollars of real estate and infrastructure will become worthless, and the consequences of those shifts will shake our economy the way a dog shakes a rat. Though those don’t mean the end of the world, they do mean that a lot of hopes and dreams are burning and there isn’t enough water left in the reservoir to put out the flames.

Meanwhile, unnoticed by most people, the price of oil continues to mount upwards. It was fashionable a little while ago to insist that renewables have become so economical that demand for oil would peak soon, leading to an easy market-driven transition away from petroleum. That and a range of political pressures led major oil companies to cut back sharply on exploration and development of new oilfields to make up for the depletion of existing reserves. Unfortunately renewables have once again proven unable to pick up the slack. With the world currently using well over 100 million barrels of crude oil a day to power its transport networks and keep industries supplied with raw materials, supply and demand has taken over in the usual way.

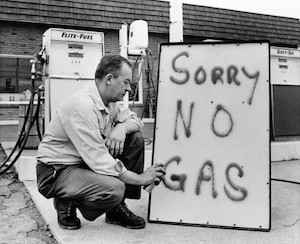

Remember this?On schedule, we’re seeing soaring prices for food and spot shortages on store shelves. Those of my readers who remember the oil crises of 1973 and 2008 know that these are among the usual warning signs. I expect to see the prices of petroleum products for consumers spike hard next year. They’ll come back down, but not all the way, and by the time they do so, another large fraction of Americans will have been driven down into permanent poverty, to join those driven down by the last two energy crises. Since thirty-five years passed between the first two energy crises and we’re coming up on half that as the next one builds, the interval between crises appears to be shrinking steadily. If that continues, the next few decades are going to be rough.

Remember this?On schedule, we’re seeing soaring prices for food and spot shortages on store shelves. Those of my readers who remember the oil crises of 1973 and 2008 know that these are among the usual warning signs. I expect to see the prices of petroleum products for consumers spike hard next year. They’ll come back down, but not all the way, and by the time they do so, another large fraction of Americans will have been driven down into permanent poverty, to join those driven down by the last two energy crises. Since thirty-five years passed between the first two energy crises and we’re coming up on half that as the next one builds, the interval between crises appears to be shrinking steadily. If that continues, the next few decades are going to be rough.

The human imagination is a powerful tool for confronting these crises and envisioning ways to cope with them. The first step in putting it to work in that necessary task, however, is to ditch the fantasy that we can expect a miracle to bail us out of the mess we’ve made for ourselves. All of us, and especially those of us in the comfortable classes, are going to have to get by with much less energy and much less of the products of energy -- yes, that’s spelled “goods and services” in plain English -- than we’re used to. All of us are going to have to deal with unfamiliar constraints and challenges. That’s work that the human imagination is well equipped to handle, so long as it shakes off the overblown sense of entitlement that leads people to think the universe will cater to their cravings, and gets to work instead on envisioning what we can still accomplish with the time and dwindling resources we have left.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served twelve years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.