The Wars of the Roses | John Michael Greer

July 21, 2021 (EcoSophia.net) -- At this point in our survey of the magical history of America, we’ve reached the period that can fairly be called the golden age of American occultism.

It’s a little difficult to date the leading edge of that period, but 1890 will do as well as any. The end of the golden age is a good deal easier to place. It happened in 1929, and yes, the stock market crash of that year was one of the reasons why. The other -- well, we’ll get to that in a future post.

Several factors flowed together to make that golden age possible. Most obviously, the runaway success of the Theosophical Society in the United States and elsewhere made it clear to a great many people that there was a huge and mostly untapped market for occultism in America, and that market wasn’t even remotely satisfied with the traditions of folk magic and the volumes of divinatory party games for young ladies that made up most of what was available in American popular culture before 1890. The law of supply and demand accordingly saw to it that plenty of other orders, societies, and schools popped up to provide occult teachings for those who weren’t satisfied with what the Theosophists had to offer.

H.P. Blavatsky, would-be monopolist.As the Golden Age dawned, furthermore, there were plenty of people who weren’t satisfied with Theosophy. As the Theosophical Society expanded, Blavatsky and her successors made the same mistake that Bill Gates made more recently in a different field. Instead of competing with her rivals by providing better goods and services, she tried to enforce a monopoly over the industry and force consumers to accept whatever she chose to offer, because it was the ony game in town. That never works for long. For the same reason that you probably don’t use Internet Explorer any more, a great many Americans interested in occultism bailed out on Theosophy as soon as a more appealing alternative came into sight. That made life easy for anybody who could come up with a more appealing alternative -- and plenty of people accordingly did.

H.P. Blavatsky, would-be monopolist.As the Golden Age dawned, furthermore, there were plenty of people who weren’t satisfied with Theosophy. As the Theosophical Society expanded, Blavatsky and her successors made the same mistake that Bill Gates made more recently in a different field. Instead of competing with her rivals by providing better goods and services, she tried to enforce a monopoly over the industry and force consumers to accept whatever she chose to offer, because it was the ony game in town. That never works for long. For the same reason that you probably don’t use Internet Explorer any more, a great many Americans interested in occultism bailed out on Theosophy as soon as a more appealing alternative came into sight. That made life easy for anybody who could come up with a more appealing alternative -- and plenty of people accordingly did.

The other factor that helped pup an abundance of new occult schools as the golden age dawned was the revolution in transport that flung railways across the North American continent in the third quarter of the 19th century. It took a little while for the post office to catch up with that revolution, but well before 1890 any mail that went outside a single urban area went by train. Postal cars -- in effect, post offices on wheels, where mail was sorted and bagged for its destinations by postal clerks while en route -- took over much of the mail, cutting delivery times to a fraction of what they had been. All of a sudden letters and packages could be shipped promptly and safely from one end of the United States to the other in a matter of a few days. That in turn led to the rise of the correspondence course industry.

drafting lessonsTurn to the back pages of any magazine published between 1890 and the rise of television, accordingly, and you can count on finding scores of advertisements for correspondence courses on any subject you care to think of. Interested in learning accounting? Here you go. Want to play the piano? Step right up. How about improving your memory? We’ve got you covered. What about the secrets of the ages, passed down by a long line of occult masters from Egypt or Atlantis or what have you? Send a self-addressed envelope and $1.00 to Scribe XYZ for an application for our correspondence course. What this meant is that any enterprising occult teacher could have a nationwide audience for his or her teaching for the cost of a classified ad. Plenty of enterprising occult teachers did exactly this -- and countless thousands of aspiring students of occultism duly sent in their self-addressed envelopes and dollar bills, applied for membership, and took in weekly or monthly lessons thereafter.

drafting lessonsTurn to the back pages of any magazine published between 1890 and the rise of television, accordingly, and you can count on finding scores of advertisements for correspondence courses on any subject you care to think of. Interested in learning accounting? Here you go. Want to play the piano? Step right up. How about improving your memory? We’ve got you covered. What about the secrets of the ages, passed down by a long line of occult masters from Egypt or Atlantis or what have you? Send a self-addressed envelope and $1.00 to Scribe XYZ for an application for our correspondence course. What this meant is that any enterprising occult teacher could have a nationwide audience for his or her teaching for the cost of a classified ad. Plenty of enterprising occult teachers did exactly this -- and countless thousands of aspiring students of occultism duly sent in their self-addressed envelopes and dollar bills, applied for membership, and took in weekly or monthly lessons thereafter.

There was inevitably a great deal of competition in the field. The intensity of the competition varied from one branch of occultism to another, largely depending on who claimed which ancient occult heritage and how willing they were to launch a public squabble over it. The fiercest and most colorful of all the resulting struggles centered around the legacy of the old Rosicrucians, and the conflicts, in a wry reference to the English civil wars of the 15th century, have been called the Wars of the Roses.

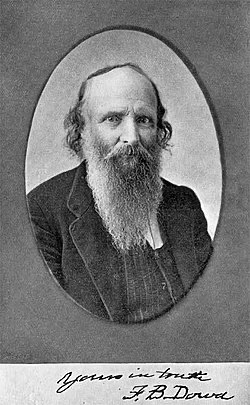

Freeman B. DowdLet’s start by setting out the contending forces. The oldest of the lot, in corner #1, is the Fraternitas Rosae Crucis (“Fraternity of the Rose Cross” in Latin) or F.R.C., which we last saw as one of the creations of that force of nature, Paschal Beverly Randolph. He originally founded it in 1858, but his “cross-grained” nature kept it from becoming much more than a scattered network of students until after his death in 1875, when Randolph’s student Freeman B. Dowd reorganized it, becoming its second Supreme Grand Master. In 1907 Edward H. Brown succeeded him, and in 1922 the mantle passed to an osteopathic doctor named Reuben Swinburne Clymer, who had joined the order in 1897 and had been helping to run it since 1905; he remained in charge until his death in 1966. When he became its head, its headquarters moved to Clymer’s home town, Quakertown, Pennsylvania, where it remains today.

Freeman B. DowdLet’s start by setting out the contending forces. The oldest of the lot, in corner #1, is the Fraternitas Rosae Crucis (“Fraternity of the Rose Cross” in Latin) or F.R.C., which we last saw as one of the creations of that force of nature, Paschal Beverly Randolph. He originally founded it in 1858, but his “cross-grained” nature kept it from becoming much more than a scattered network of students until after his death in 1875, when Randolph’s student Freeman B. Dowd reorganized it, becoming its second Supreme Grand Master. In 1907 Edward H. Brown succeeded him, and in 1922 the mantle passed to an osteopathic doctor named Reuben Swinburne Clymer, who had joined the order in 1897 and had been helping to run it since 1905; he remained in charge until his death in 1966. When he became its head, its headquarters moved to Clymer’s home town, Quakertown, Pennsylvania, where it remains today.

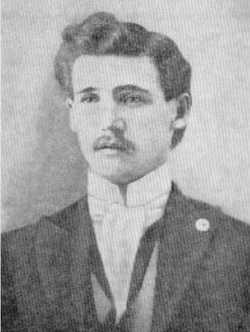

Reuben Swinburn Clymer

Reuben Swinburn Clymer

Clymer was an American occultist of a classic type, just as deep into alternative heatlh care and diet as he was into spiritual practice. An opponent of vaccination and chemical medicine, he favored herbal healing and argued that red meat is toxic but fish, dairy foods, and eggs are healthy. In the occult end of his work, he devoted much of his life to synthesizing and developing P.B. Randolph’s teachings, and developing a series of orders and churches to embody the different aspects of the teachings, as well as writing two lengthy correspondence courses that are still available. He believed that as head of the F.R.C. he was the legitimate head of the Rosicrucian tradition in America, and he was not the kind of person who could handle having his prerogatives challenged.

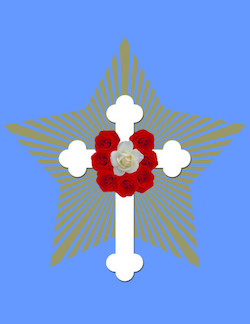

The SRIA’s emblemIn corner #2 is the Societas Rosicruciana in America (SRIA), which also connects to a current we’ve already traced. Sylvester Clark Gould, an American Freemason and student of occultism in Manchester, New Hampshire, was a member of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor in its brief heyday, and also belonged to a short-lived American branch of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, the premier Masonic Rosicrucian order. (Another American branch was founded later and still exists today.) When the H.B. of L. collapsed, Gould made contact with a Rosicrucian order in Hungary, received the necessary initiations to start a Rosicrucian organization of his own, launched a periodical named The Rosicrucian Brotherhood, and passed on his initiations to several other Masons with occult interests. Before his intended organization could get started, however, Gould died.

The SRIA’s emblemIn corner #2 is the Societas Rosicruciana in America (SRIA), which also connects to a current we’ve already traced. Sylvester Clark Gould, an American Freemason and student of occultism in Manchester, New Hampshire, was a member of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor in its brief heyday, and also belonged to a short-lived American branch of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, the premier Masonic Rosicrucian order. (Another American branch was founded later and still exists today.) When the H.B. of L. collapsed, Gould made contact with a Rosicrucian order in Hungary, received the necessary initiations to start a Rosicrucian organization of his own, launched a periodical named The Rosicrucian Brotherhood, and passed on his initiations to several other Masons with occult interests. Before his intended organization could get started, however, Gould died.

George Winslow PlummerGeorge Winslow Plummer, who had received the initiations from Gould, went ahead with the project and founded the SRIA in 1909. From then until his death in 1944 he was one of the fixtures of the occult scene in New York City, a frequent lecturer and the author of books on New Thought and Rosicrucian spirituality. The Metropolitan College of the SRIA, the New York lodge of the society, taught astrology, meditation, and mystical Christianity to local students, while the SRIA correspondence course passed on his occult philosophy to students around the country. A series of other Colleges sprang up in towns and cities elsewhere in the United States and also in Freetown, Liberia. In addition, Plummer arranged to be ordained as a priest and then consecrated as a bishop in one of the independent Orthodox Christian churches.

George Winslow PlummerGeorge Winslow Plummer, who had received the initiations from Gould, went ahead with the project and founded the SRIA in 1909. From then until his death in 1944 he was one of the fixtures of the occult scene in New York City, a frequent lecturer and the author of books on New Thought and Rosicrucian spirituality. The Metropolitan College of the SRIA, the New York lodge of the society, taught astrology, meditation, and mystical Christianity to local students, while the SRIA correspondence course passed on his occult philosophy to students around the country. A series of other Colleges sprang up in towns and cities elsewhere in the United States and also in Freetown, Liberia. In addition, Plummer arranged to be ordained as a priest and then consecrated as a bishop in one of the independent Orthodox Christian churches.

Max HeindelPlummer’s Rosicrucian teachings had a lot of shared ground with those of the next order on the list, the Rosicrucian Fellowship over in corner #3, which was also founded in 1909. Its founder was Danish occultist Carl von Grasshof, who moved to the United States in 1903 and later changed his name to Max Heindel. Heindel was an astrologer and Theosophist who studied with California teacher Katherine Tingley and iconic Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner, and set out to teach a Western occult spirituality that was accessible to the general public. His organization was originally founded in Seattle, but he moved to Oceanside, California, where the Rosicrucian Fellowship is headquartered today.

Max HeindelPlummer’s Rosicrucian teachings had a lot of shared ground with those of the next order on the list, the Rosicrucian Fellowship over in corner #3, which was also founded in 1909. Its founder was Danish occultist Carl von Grasshof, who moved to the United States in 1903 and later changed his name to Max Heindel. Heindel was an astrologer and Theosophist who studied with California teacher Katherine Tingley and iconic Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner, and set out to teach a Western occult spirituality that was accessible to the general public. His organization was originally founded in Seattle, but he moved to Oceanside, California, where the Rosicrucian Fellowship is headquartered today.

The Rosicrucian Fellowship teaches mystical Christianity and astrology, and its members are encouraged to adopt celibacy and a vegetarian diet and to give up alcohol, tobacco and drugs. Heindel wrote a good-sized shelf of books on occult and astrological topics, but the one that mattered most was The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, which has since become one of the classics of American occultism. He also penned correspondence courses which are made available to students on a by-donation basis. He died in 1919, but his organization continued to thrive thereafter under the capable guidance of his widow Augusta Heindel.

The Rosicrucian Fellowship teaches mystical Christianity and astrology, and its members are encouraged to adopt celibacy and a vegetarian diet and to give up alcohol, tobacco and drugs. Heindel wrote a good-sized shelf of books on occult and astrological topics, but the one that mattered most was The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, which has since become one of the classics of American occultism. He also penned correspondence courses which are made available to students on a by-donation basis. He died in 1919, but his organization continued to thrive thereafter under the capable guidance of his widow Augusta Heindel.

The Manly One in his younger days.Heindel’s organization had an outsized impact on the world of occultism through three indirect means. The first was a young Canadian man named Manly Palmer Hall, who came to California in 1919 and stayed with the Heindels for a short time before Max died. Hall went on to become far and away the most influential occultist of mid-20th century America, a titanic figure with an outsized influence on his society and era, and if you know his work you can see the themes he learned from Max Heindel’s teachings all through it.

The Manly One in his younger days.Heindel’s organization had an outsized impact on the world of occultism through three indirect means. The first was a young Canadian man named Manly Palmer Hall, who came to California in 1919 and stayed with the Heindels for a short time before Max died. Hall went on to become far and away the most influential occultist of mid-20th century America, a titanic figure with an outsized influence on his society and era, and if you know his work you can see the themes he learned from Max Heindel’s teachings all through it.

The second was the aforementioned George Winslow Plummer. Unusually for an occultist of his time, Plummer didn’t think he was the only valid Rosicrucian in the market; he considered Heindel and Steiner as reputable Rosicrucian authorities and cited them by name and page number in his own works. Since his SRIA didn’t require vegetarianism and celibacy, it drew a great many students who were interested in Rosicrucian occultism but weren’t interested in these two strictures, and those students got a fair amount of secondhand Heindel when they didn’t just plop for a copy of The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception as additional reading for their studies.

Hugo VollrathThe third indirect route was less honest and a good deal funnier. A German Theosophist named Hugo Vollrath was the channel in question. He ran the Theosophical Publishing House in Leipzig, Germany until it was shut down on Hitler’s orders. A classic occult eccentric, he liked to wear a fez because, he said, it kept his aura in place. Like a great many occultists of his time, he founded a correspondence school; like the groups we’ve discussed already, his borrowed the Rosicrucian name and label. Instead of going to the trouble of coming up with his own teachings, he translated passages from Max Heindel’s writings and sent them out as “Master Letters” under the nom de adeptship of Walter Heilmann. The “Master Letters” spread far and wide, and quite a few people who later claimed other origins for their teachings got their introduction to Rosicrucian occultism from them.

Hugo VollrathThe third indirect route was less honest and a good deal funnier. A German Theosophist named Hugo Vollrath was the channel in question. He ran the Theosophical Publishing House in Leipzig, Germany until it was shut down on Hitler’s orders. A classic occult eccentric, he liked to wear a fez because, he said, it kept his aura in place. Like a great many occultists of his time, he founded a correspondence school; like the groups we’ve discussed already, his borrowed the Rosicrucian name and label. Instead of going to the trouble of coming up with his own teachings, he translated passages from Max Heindel’s writings and sent them out as “Master Letters” under the nom de adeptship of Walter Heilmann. The “Master Letters” spread far and wide, and quite a few people who later claimed other origins for their teachings got their introduction to Rosicrucian occultism from them.

Harvey Spencer LewisThen there’s the final contender in the Wars of the Roses, the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (AMORC) in corner #4. AMORC was the creation of Harvey Spencer Lewis, a New York commercial artist with a longtime interest in occultism and parapsychology. In later years he insisted that he received a charter from a Rosicrucian order in France in 1909. In terms of the kind of history that can actually be documented, he applied for membership in the SRIA in 1914, and his application was rejected. The next year he contacted Swiss occultist Theodor Reuss, the head of the Ordo Templi Orientis -- another offshoot of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor -- and got a charter from him.

Harvey Spencer LewisThen there’s the final contender in the Wars of the Roses, the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (AMORC) in corner #4. AMORC was the creation of Harvey Spencer Lewis, a New York commercial artist with a longtime interest in occultism and parapsychology. In later years he insisted that he received a charter from a Rosicrucian order in France in 1909. In terms of the kind of history that can actually be documented, he applied for membership in the SRIA in 1914, and his application was rejected. The next year he contacted Swiss occultist Theodor Reuss, the head of the Ordo Templi Orientis -- another offshoot of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor -- and got a charter from him.

Aleister Crowley in his younger days.Lewis may not have realized this at the time, but he was stumbling into a hornet’s nest of occult politics. Some years previously Reuss had given a charter to English occultist Aleister Crowley, only to discover that Crowley assumed that the charter gave him the right to run the entire order according to his own eccentric lights. Reuss’ contacts with Lewis were meant to help take the OTO back from Crowley and his Canadian protegé Charles Stansfield Jones. Crowley proceeded to make contact with Lewis and made various offers, which Lewis had the good sense to turn down. Reuss, for his part, conferred a great many titles and ranks on Lewis, but his demands for money were unceasing. Finally Lewis had had enough, and in 1925 he founded his own organization, AMORC. Originally based in Florida, it relocated to San José, California in 1927.

Aleister Crowley in his younger days.Lewis may not have realized this at the time, but he was stumbling into a hornet’s nest of occult politics. Some years previously Reuss had given a charter to English occultist Aleister Crowley, only to discover that Crowley assumed that the charter gave him the right to run the entire order according to his own eccentric lights. Reuss’ contacts with Lewis were meant to help take the OTO back from Crowley and his Canadian protegé Charles Stansfield Jones. Crowley proceeded to make contact with Lewis and made various offers, which Lewis had the good sense to turn down. Reuss, for his part, conferred a great many titles and ranks on Lewis, but his demands for money were unceasing. Finally Lewis had had enough, and in 1925 he founded his own organization, AMORC. Originally based in Florida, it relocated to San José, California in 1927.

AMORC’s emblem. (If you’re wondering where the FRC emblem is, they deliberately don’t have one.)As a commercial artist, Lewis had done a great deal of work in the advertising industry, and he understood marketing to a degree that few other occultists of his time could match. Once the AMORC correspondence course got under way, Lewis flooded popular magazines with full page advertisements, and for a while had his own radio station to help proclaim the Rosicrucian gospel across the airwaves. That inevitably brought him to the attention of Clymer, who responded with fury to Lewis’ claims, and the war was on.

AMORC’s emblem. (If you’re wondering where the FRC emblem is, they deliberately don’t have one.)As a commercial artist, Lewis had done a great deal of work in the advertising industry, and he understood marketing to a degree that few other occultists of his time could match. Once the AMORC correspondence course got under way, Lewis flooded popular magazines with full page advertisements, and for a while had his own radio station to help proclaim the Rosicrucian gospel across the airwaves. That inevitably brought him to the attention of Clymer, who responded with fury to Lewis’ claims, and the war was on.

The first round was carried out by proxies. Two disaffected members of AMORC, George Smith and Alfred Saunders, had launched their own campaigns of negative publicity against Lewis and his organization, and Clymer leapt on their bandwagon and gave as much publicity as he could to their charges. Lewis responded by publishing a book, Audi Alterem Partem (“hear the other side” in Latin -- Lewis had a habit of using Latin for his official pronouncements) which purported to be a response to Clymer’s accusations by a committee called to investigate them; the committee, of course, found them groundless. Lewis’ book also called Clymer a bogus occultist whose fondness for grandiose titles had led him into the fake-Rosicrucian business.

books

books

Clymer went ballistic. He had previously published volume 1 of The Rosicrucian Fraternity in America, a history of American Rosicrucianism which of course stressed the importance of his order. The second volume, all 959 pages of it, was an all-out assault on Lewis and AMORC. Lewis responded in kind, though not at the same length, with an assortment of published jabs at Clymer. It’s entertaining to note that both men accused the other of teaching sex magic, and both tried to associate the other with Aleister Crowley, whose antics had given the scandal sheets of their time an ample supply of lurid stories in the decades just past.

As part of his counterattack, Lewis set out to give his order a less controversial connection with European Rosicrucian orders. In 1934 he and a Belgian occult promoter named Jean Malinger created an organization called the Federatio Universalis Dirigens Ordines Societatesque Initiationis (Universal Directing Federation of Initiatory Orders and Societies), mercifully shortened to FUDOSI in common parlance. Not to be outdone, Clymer launched the Federation Universelle des Ordres, Sociétés et Fraternités de Initiés (Universal Federation of Orders, Societies, and Fraternities of Initiates) or FUDOFSI, and published another volume titled The Book of Rosicruciae in which he described his travels around the world and his meetings with the Rosicrucian societies that had honored him as the one true representative of the Rose Cross in North America.

Clymer in his mellower old age.The back and forth between the two men continued until Lewis’ death in 1939. Clymer continued taking pot shots at AMORC after Lewis’ son Ralph took over the organization, but the old fire was gone, and the FRC had other threats to cope with once the federal government began its crackdown on alternative health care after the Second World War. For its part, AMORC under Ralph Lewis and his successors embraced the wiser strategy of ignoring its critics, and went on to have a substantial influence on American occultism and society in general. Did you know, for example, that Walt Disney was a member of AMORC?

Clymer in his mellower old age.The back and forth between the two men continued until Lewis’ death in 1939. Clymer continued taking pot shots at AMORC after Lewis’ son Ralph took over the organization, but the old fire was gone, and the FRC had other threats to cope with once the federal government began its crackdown on alternative health care after the Second World War. For its part, AMORC under Ralph Lewis and his successors embraced the wiser strategy of ignoring its critics, and went on to have a substantial influence on American occultism and society in general. Did you know, for example, that Walt Disney was a member of AMORC?

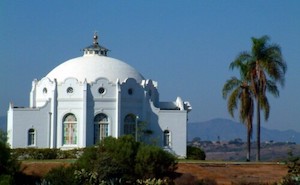

The Rosicrucian Fellowship’s headquarters.

The Rosicrucian Fellowship’s headquarters.

Interestingly, neither of the rival orders directed much rhetorical ammunition at the other two Rosicrucian orders we’ve mentioned. The Lewises serenely ignored everyone but Clymer, who was too good at jabbing it in painful places to get the same treatment, while Clymer made dismissive comments about the SRIA and Rosicrucian Fellowship from time to time but didn’t follow up on them. For their part, Plummer and Augusta Heindel acted as though the whole controversy was someone else’s problem, and it accordingly was.

AMORC’s American headquarters.The rivalry we have chronicled had its positive dimensions, to be sure. The two orders built competing parks on opposite sides of the continent -- the grounds of Beverly Hall in Quakertown PA, and Rosicrucian Park in San Jose CA. Both are full of ornate architecture and facilities for their respective organizations, and both became sites of pilgrimage for their respective students. Both of them are worth a visit if you happen to be in the area. So, for that matter, is Mount Ecclesia in Oceanside, California, the headquarters of the Rosicrucian Fellowship, another park with ornate buildings. Few other organizations active in the golden age of American occultism managed that kind of monument to themselves. I’m sorry to say that our fourth competitor, the SRIA, never got around to building a spacious headquarters in a park, and currently operates out of a private home in a Florida suburb. Many other once-mighty occult orders have been reduced to similar straits if they have managed to survive at all.

AMORC’s American headquarters.The rivalry we have chronicled had its positive dimensions, to be sure. The two orders built competing parks on opposite sides of the continent -- the grounds of Beverly Hall in Quakertown PA, and Rosicrucian Park in San Jose CA. Both are full of ornate architecture and facilities for their respective organizations, and both became sites of pilgrimage for their respective students. Both of them are worth a visit if you happen to be in the area. So, for that matter, is Mount Ecclesia in Oceanside, California, the headquarters of the Rosicrucian Fellowship, another park with ornate buildings. Few other organizations active in the golden age of American occultism managed that kind of monument to themselves. I’m sorry to say that our fourth competitor, the SRIA, never got around to building a spacious headquarters in a park, and currently operates out of a private home in a Florida suburb. Many other once-mighty occult orders have been reduced to similar straits if they have managed to survive at all.

The FRC’s headquarters.All four of the Rosicrucian orders discussed here, for that matter, are still in existence and still offer correspondence courses to aspirants. The current AMORC course, according to members I know, has been completely rewritten several times since Harvey Spencer Lewis’ day, while the other three still pass on the teachings of Clymer, Plummer, and Heindel respectively in unabridged form. Readers interested in various ends of alternative culture may be interested to know that the FRC still adamantly opposes vaccination and promotes natural healing, and the SRIA and the Rosicrucian Fellowship continue to teach their own somewhat quirky forms of mystical Christianity to anyone who is willing to learn.

The FRC’s headquarters.All four of the Rosicrucian orders discussed here, for that matter, are still in existence and still offer correspondence courses to aspirants. The current AMORC course, according to members I know, has been completely rewritten several times since Harvey Spencer Lewis’ day, while the other three still pass on the teachings of Clymer, Plummer, and Heindel respectively in unabridged form. Readers interested in various ends of alternative culture may be interested to know that the FRC still adamantly opposes vaccination and promotes natural healing, and the SRIA and the Rosicrucian Fellowship continue to teach their own somewhat quirky forms of mystical Christianity to anyone who is willing to learn.

All four orders also have a significant presence online. You’ll find the FRC at soul.org, the SRIA at sria.org, the Rosicrucian Fellowship at rosicrucianfellowship.org, and AMORC at amorc.org. The era of open hostility among the orders has slipped far into the past, though the FRC still aims the occasional pot shot at AMORC for old times’ sake, and the SRIA quietly keeps Harvey Spencer Lewis’ 1914 application up on their website. It’s a genteel echo of a far more colorful age.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served twelve years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.

- CategoriesEdited | Commentary -- WNT Original | Commentary | Europe | Asia | North America | Entertainment | Arts | Culture | All Content | Front Page Stories

- CreatedTuesday, July 27, 2021

- Last modifiedWednesday, July 28, 2021

SUBSCRIBE

World Desk Activities

www.imf.org/en/News/Podcasts/All-Podcasts/2024/05/…

en.vedur.is/about-imo/news/volcanic-unrest-grindav…

www.sciencealert.com/shift-in-indias-vulture-popul…

Shift in India's Vulture Population Linked to Half a Million Human Deaths : ScienceAlert

A cattle painkiller introduced in the 1990s led to the unexpected crash of India's vulture populations, which still haven't recovered to their former glory.

Latest Stories

Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Digital Apartheid in Gaza: Unjust Content Moderation at the Request of Israel’s Cyber Unit July 26, 2024

- Electronic Frontier Foundation to Present Annual EFF Awards to Carolina Botero, Connecting Humanity, and 404 Media July 25, 2024

- Briefing: Negotiating States Must Address Human Rights Risks in the Proposed UN Surveillance Treaty July 24, 2024

- Journalists Sue Massachusetts TV Corporation Over Bogus YouTube Takedown Demands July 24, 2024

The Conversation

- Vale Ray Lawler: the playwright who changed the sound of Australian theatre

- Magnificent and humbling: the Paris opening ceremony was a tribute to witnessing superhuman feats of the extraordinary

- How collaboration from across Canada, and the world, is helping fight the Alberta wildfires

- Paris Olympics: Canada’s soccer drone scandal highlights the need for ethics education

The Intercept

- Honduras, 15 Years After the Coup: An Interview With Ousted President Manuel Zelaya July 26, 2024

- Google Planned to Sponsor IDF Conference That Now Denies Google Was Sponsor July 25, 2024

- Deputy Accused of Killing Sonya Massey Was Discharged From Army for Serious Misconduct July 25, 2024

- U.S. Has Never Apologized to Somali Drone Strike Victims — Even When It Admitted to Killing Civilians July 25, 2024

VTDigger

- Waterbury residents looked to FEMA buyouts after last year’s floods. They’ve heard nothing for months July 26, 2024

- At a quiet Craftsbury pond, rowers become Olympians July 26, 2024

- UVM Medical Center wins approval to buy Fanny Allen Campus July 26, 2024

- Landslides and slurries have damaged homes, roads and driveways after this month’s flood July 26, 2024