Then there’s Jen Psaki, spokesflack-in-chief for poor bumbling Joe Biden. She was asked by a reporter at a recent presser about the people, and of course there are a great many of them, who are increasingly worried about the future of the United States under Biden’s inept leadership. Her response? “My advice to everyone out there who’s frustrated, sad, angry, pissed off, feel those emotions, go to a kickboxing class, have a margarita.”

For sheer crazed detachment from the world the rest of us inhabit, that’s hard to beat, especially when you recall that her boss campaigned saying he would, you know, fix the country’s problems. Maybe her words make more sense in German, or for that matter in pig Latin, but I doubt it.

What all this brings to mind, of course, is the climactic scene in C.S. Lewis’s tremendous fantasy That Hideous Strength. The villains of the piece, a collection of arrogant technocrats among whom Psaki and Lauterbach would fit in seamlessly, are gathered at their headquarters at Belbury for a banquet. What they don’t know is that their attempts to get control of certain supernatural forces have stirred up old strong magics from the Arthurian era, and Merlin -- yes, that Merlin -- is on the scene.

The first spell he casts on them is the same one that made life so interesting for the construction crews at the Tower of Babel. While this is taking effect, and their speech is turning into the kind of absurdity we were just discussing, Merlin works his second spell, which makes good use of the well-stocked collection of experimental animals at the facility. Some of these are decidedly large, fierce, and hungry. The survival rate for the villains -- well, we don’t have to get into that; let’s just say the beasts go away well fed.

Literary parallels are always chancy things, and I’m by no means sure just how far to take this one. Certainly if any 6th-century Roman-British wizards have been revived recently, my contacts in the British occult community haven’t let me know about it yet, and our current crop of arrogant technocrats haven’t actually gotten around to naming themselves the National Institute for Coordinated Experiments, though doubtless Klaus Schwab will get to that shortly.

That said, there’s enough in common between the utterances of Lewis’s villains and those we’ve just surveyed that we might as well describe the latter as cases of Belbury Syndrome. After all, if Jen Psaki were to get up in front of the microphones next week and confidently announce, “The madrigore of verjuice must be talithibianised,” I can’t say I’d be surprised. If I were her or Lauterbach, I’d keep an eye out for hungry beasts.

All jesting aside, the two remarks quoted earlier are worth keeping in mind, not least because they’re anything but unique. We’ve all heard politicians and media flacks insisting with straight faces, for example, that the Covid-19 pandemic can only be stopped by getting more people to take vaccines that don’t stop anyone from catching the virus or transmitting it to others.

Other examples are as close as your nearest corporate media venue. I’ve written about this from various angles in the past, of course, suggesting various ways to get out from under the weird collective trance that grips the managerial aristocracy of the modern industrial world these days.

It seems to me just now, however, that there’s a very simple way to talk about the accelerating collapse of meaning that’s afflicting our self-proclaimed lords and masters. What we’re seeing is a terminal failure of the imagination.

Modern industrial society’s attitude toward imagination is frankly weird, a volatile mixture of nostalgia, condescension, and contempt. Children, artists, and “primitive” peoples -- this latter label is slapped on those ethnic groups that are less dependent on factory-made technological gimmickry than the rest of us -- are expected or even encouraged to be imaginative.

The same label of “imaginative,” and the same expectations and encouragement, used to be applied to women not that many decades ago, and it’s been instructive to watch the way that women in the comfortable classes of modern industrial society have gone out of their way to shed that label on their way to their current level of wealth and influence. If you needed a hint that “imaginative” is not a compliment in modern society, well, there you have it.

Calling some person or group of people imaginative, rather, allows them to be treated by the mainstream as second-class human beings whose insights and perceptions can be dismissed out of hand. Serious, mature, respectable people are supposed to keep whatever stray scraps of imagination they might have left neatly ghettoized in some isolated corner of their lives where it doesn’t get in the way of serious, mature, respectable discussion and decision.

In many contexts today, to call someone’s ideas “imaginative” is to dismiss them as wrong. To call something “imaginary” is to say that it doesn’t exist.

All this begs a galaxy of questions, and we can start with the most basic of them. What exactly is this thing that we’re calling “imagination?"

There are various ways that we can approach that question. I trust none of my readers will be too surprised, however, if I start with an option that doesn’t share the usual modern prejudices on the subject.

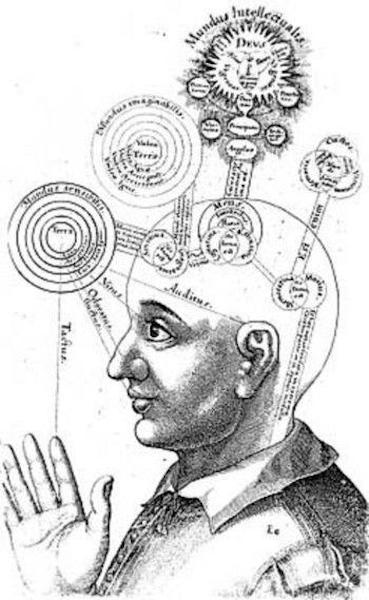

The image above is one of the famous engravings from Robert Fludd’s great 1617 encyclopedia of Renaissance occultism, Utriusque Cosmi Historia (A History of Both Worlds -- the two worlds in question being the world around us and the world within us.) It’s a schematic diagram that sums up everything that human beings can experience or think about.

The set of nested circles on the far left, up in front of the forehead, is the mundus sensibilis, the realm of perceptions brought to us by the five material senses -- notice the lines running from that set of circles to the eye, ear, nose, and so on. That’s what most people call the “real world;” right now we don’t have to get into the reasons why it’s much less real than it looks.

The set above and to the right of the mundus sensibilis is the mundus imaginabilis, the realm of perceptions brought to us by the imaginative equivalents of the ordinary senses. It’s divided into rings identical to those of the mundus sensibilis, and each of these rings is labeled as a shadow of one of the rings of the mundus sensibilis.

That’s the key to the imagination in Fludd’s view. For him, and for the many other psychologists of his time and the centuries before then, the imaginative world is made up of sensations that don’t come to you by way of your five material senses, but they have the same forms as the products of those senses.

You can put this to the test easily enough. Take a moment, right now, to imagine a bright blue, slightly luminous cat walking past you. Each of its footfalls makes a crunching noise, and from it radiates a pervasive feeling of cold and a scent of peppermint.

This isn’t something you’re ever likely to perceive with your material senses -- if it is, you may want to get your glasses checked in a hurry! -- but you just imagined it as I described it, didn’t you? Every detail you assigned to it, from the blue color to the scent of peppermints, was borrowed via memory from sensations you’ve previously experienced. You simply took these remembered sensations (blue, crunch, etc.) and assembled them in a new way.

If you want to test the limits of imagination, try imagining a new primary color: not a blend of any other colors you have ever seen, but a color different from all other colors, as different as red is from blue. I’ll offer you a hint: you can’t.

You might be able to come up with the abstract notion of another primary color -- David Lindsay, a brilliant and mostly forgotten author of imaginative fiction, did this with fine effect in his 1920 novel A Voyage to Arcturus, giving the distant world on which his story is set the two additional primary colors of jale and ulfire -- but it remains an abstraction. You can’t even really imagine the extra colors seen by bees, whose eyes reach parts of the spectrum ours can’t: that’s why those extra colors are called “bee purple” and the like, to give a metaphoric label to something humans can’t actually imagine.

What all this means, to use a term I’ve referenced several times in recent posts, is that imagination is a mode of figuration. Figuration, as you may recall from those earlier posts, is Owen Barfield’s term for the process by which we assemble the raw material of sensation into a set of objects that, for us, comprise the world.

We learn to turn sensations into figurations in earliest infancy by a process of trial and error, and after many corrections and mistakes get sufficiently good at it that we scarcely notice doing it. Thereafter, only certain optical illusions and the occasional experience of mistaking one thing for another shows us just how much mental effort goes into creating what we think of as objective reality.

To imagine something, in turn, is to use the same process on remembered sensations to construct figurations of things that don’t happen to be present. We learn this in earliest infancy, too, and get just as good at it. If you think about what you’re going to do tomorrow, and call to mind the errands you plan on running, the people you hope to meet, and the glass of hot buttered rum you plan on drinking to take off the chill once you drag yourself home again, you’re using your imagination.

If, without turning your head, you turn your attention to the room behind you, you’re using your imagination then, too. Anything that’s part of your world, but isn’t actually in range of your five material senses? Once again, when you turn your mind to them, you’re using your imagination.

Most of the time, again, you don’t notice that you’re doing it. Deliberate efforts to imagine something fill the same role here as optical illusions and mistaken identities do for sensory figurations: they show us that something we take for granted as “out there” really is constructed by our own thinking.

The close connection between sensory figuration and imaginative figuration is why Fludd’s diagram shows the mundus sensibilis and the mundus imaginabilis projected from a pair of overlapping circles in the front of the head. They’re not the same, but they can’t be separated: the matrix of representations that you think of as the world is figurated partly using the things your senses tell you, and partly using the things your imagination tells you.

Your emotions and your body, by the way, respond equally strongly to figurations from both sources. If you think the noises you hear outside the window were made by a wild beast, or for that matter by Karl Lauterbach skulking outside with a syringe in his hand and a maniacal cackle on his lips, that will get your heart pounding and your adrenaline going whether the noises are caused by a hungry wild beast, a crazed technocrat, or just the wind rattling branches against the wall.

From the overlapping circles of sensation and imagination, in turn, a link goes back to the more complex structure at the middle of the head, which is the human capacity for thought. Fludd, like the other psychologists of his time, divides that into two factors, understanding and judgment.

On top of those are three additional circles -- reason, intuition, and enlightenment -- which, in the view of Fludd and the other psychologists of his time, were the products of education rather than nature. The highest of those, and only the highest of them, comes close to the complex flurry of shapes above, which represents the spiritual world. (Fludd, like most Renaissance occultists, was a Christian, and so he portrayed this in standard Christian terms as the Trinity and the nine choirs of angels.)

You’ll notice that the band descending from this doesn’t actually go into the head: even enlightenment, in this way of thinking, doesn’t breach the inescapable barrier between representation and reality or, in Fludd’s terms, between the creature and the Creator.

The third set of overlapping circles further back? Those are the purely mechanical operations of the brain, which Fludd calls its memorative and motive functions: in our somewhat more ungainly terms, the storage of memories and the coordination of physical motion.

The three overlapping circles above the back of the head, linked by a band to the memorative circle, are the subjective functions of memory; the band descending from the motive circle is the spinal cord, which takes the motor impulses to the muscles of the body. Yes, Renaissance occultists knew about that. Our current notion that nobody knew anything about the human body before scientists got into the act is just as dishonest as the claim that in 1492, everyone but Christopher Columbus thought that the world was flat.

If we turn back to what’s going on further forward in the head, you’ll notice that the link between perception and thought goes from imagination to cognition. Here again Fludd is quite correct. We understand only what we can imagine.

Consider Copernicus, looking up at the sky. People had been doing that for many millennia, and with few exceptions they assembled their sense data into a cosmos in which the Earth sat in the middle and the Sun, planets, and stars went around it.

Copernicus, with a mighty leap of the imagination, put the Sun at the center and spun everything else around it. That wasn’t an exercise of the understanding or the reason; again, millions of people for thousands of years had applied their cognitive capacities and their learned ability to reason to the question of how to make sense of the cosmos, and all they’d done was come up with ever more elaborate ways of making sense of an Earth-centered cosmos.

That’s what they did, and that’s all they could have done, because thinking can’t go beyond its own presuppositions. Reason can show you when your presuppositions conflict with one another, and that’s an enormous gain: the ancient Greek thinkers who first figured out how to do that systematically made a hefty contribution to human life by that act.

Science can show you when your presuppositions conflict with your figurations, and that’s another enormous gain, but science in the modern sense of the word hadn’t been invented in Copernicus’s time -- or, for that matter, in Fludd’s. Neither of them can provide you with new constellations of imagery and ideas that you can try out as a new presupposition and see how it works.

That’s what the imagination does. It creates an image or, in Fludd’s language, a shadow of the world experienced by the senses, and then plays with it, tossing the Sun from the fourth heaven to the center of the cosmos and seeing what the universe looks like in that novel configuration. It creates wholly new presuppositions and asks, “what if this were true?”

The secret of the imagination is that it’s a generator of novelty. It creates new combinations for the other functions of your mind to explore. It can work with sensations, as you found out when I had you imagine that luminous blue cat a little while back.

It can work with figurations, as Copernicus showed -- the Sun and the Earth are figurations each of us learns to construct from a gallimaufry of sensations. It can work with abstractions, as David Lindsay demonstrated by coming up with the impossible-yet-vivid idea of two more primary colors.

It can also work with other mental phenomena -- in fact, it can work with any kind of experience a human being can have.

Imagination is thus one of the basic tools of human empathy. Under most circumstances, we don’t perceive the world through anyone else’s eyes and mind but our own. There are ways around that limitation, but the most flexible and expansive of the lot is the imagination.

When you were six and your mother told you, “How would you feel if he did that to you?” -- if, in fact, she was so unfashionable as to do something so useful to your future mental health -- she was trying to get you to use your imagination, to construct from your own memories a figuration of what you would have felt if you had been in the other child’s place. That use of the imagination becomes the basis for moral reflection, and ultimately for one kind of wisdom.

That’s the kind of wisdom, moral reflection, and imagination that is so obviously absent in the two florid cases of Belbury Syndrome with which we started this discussion. If Karl Lauterbach, for example, had been capable of imagining that the people who listened to him might think about his words and try to make sense of them, rather than simply bowing and cringing the way underlings are supposed to do when one of the lords and masters of the industrial world deigns to speak to them, he would have stopped in mid-sentence, slapped himself, and said, “Mein Gott, what am I saying?”

It would have been instantly obvious to him that he was spouting nonsense; after all, when you mandate something, you are forcing it on people, and that means that, ahem, it’s not voluntary. He might even have guessed that his words would powerfully remind a great many of his listeners of the slogans from George Orwell’s novel 1984 -- “War is Peace, Slavery is Freedom, Ignorance is Strength!”

As for Jen Psaki, her case is similar. It never occurs to many people in the upper echelons of the American caste system that the people who support their extravagant lifestyles and suffer from the consequences of their decisions are actually, you know, people.

Very many of the privileged these days talk and act as though the only other people in the room are members of their own class. That’s what Psaki did. She offered the kind of helpful advice that one corporate flunkey gives to another when both of them have to put up with the annoyances of working for the same hopelessly incompetent boss.

It’s doubtless never entered her imagination that the abstract blobs out there who cast votes and hold down jobs are actual people with their own needs and hopes and dreams, who might reasonably expect Joe Biden to follow through on his campaign promises, or do something about the increasingly dismal state of life in today’s America, or at least stop making things worse. Lacking that foundation for empathy, all she could do was behave like one of the characters to whom C.S. Lewis assigned the role of tiger chow.

The collapse of imagination that stands out so clearly in the case of these two babbling technocrats is by no means limited to the corrupt ruling elite to which they both belong. Belbury Syndrome is a far more general problem just now.

Fortunately, like most other mental capacities, the imagination can be fostered and encouraged through certain methods of deliberate practice. Two weeks from now, we’ll talk about those -- and about the sweeping cultural and political implications of putting them to work.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served 12 years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.