The Flight From Thinking | John Michael Greer

Created by : John Michael Greer View profile

Silvanasono, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsApril 21, 2021 (EcoSophia.net) -- For more than a year now I’ve been devoting a post or two each month to the magical history of the United States, and I’d meant to proceed this week to another of those.

Silvanasono, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsApril 21, 2021 (EcoSophia.net) -- For more than a year now I’ve been devoting a post or two each month to the magical history of the United States, and I’d meant to proceed this week to another of those. In the unfolding story we’ve been following together, after all, we’ve reached the dawn of the golden age of American occultism, the point at which old wisdom, New Thought, and a well-stocked pantry of alternative spiritual and cultural ideas got cooked up and dished out by a gallmaufry of colorful characters as one of the grandest and most widely attended buffets in the history of magic. Still, the next phase of that story will keep. We have other things to talk about.

In a post a few weeks ago I talked about the way that some kinds of watered-down alternative spirituality have come to function as venues for a certain variety of notional dissidence on the part of our society’s privileged castes. People whose managerial jobs and six- or seven-figure salaries mark them as members of America’s comfortable classes, though they are expected to conform rigidly to the expectations of their employers and their peers in every other way, have been tacitly encouraged to take up hatha yoga or mindfulness meditation, attend shamanic retreats or weekend workshops on positive thinking, as a way of letting off steam and playing at dissent in a harmless manner.

Over the decades just past, this sort of tame dissidence has been very much in evidence, and the variety that involves meditation retreats and drumming circles is only one of several distinct types. It’s simply the type I’m most familiar with. I spent a while as the head of a Druid organization, you see, and during that stint I routinely had to fend off attempts by the privileged to turn the nature spirituality of the Druid Revival into a fashion accessory for people whose personal lifestyle choices are the mainspring behind today’s environmental problems. (The wealthiest 10 percent of the world’s population, remember -- a figure that includes all the people we’re discussing, with room to spare -- are responsible for 50 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and a comparable share of other environmental assaults.)

Just now, however, the tolerance of the establishment for these exercises in faux dissent is waning fast. As the existing structure of society falters and the supply of managerial-class jobs dwindles steadily, accusing one’s fellow inmates of thoughtcrime has become one of the most common ways to compete for the slots that are left. Alternative spiritual practices are far from the only targets for such accusations, of course; the entire woke phenomenon, for example, is primarily a way of taking words and attitudes that used to be acceptable, and weaponizing them in the no-holds-barred struggle for deck chairs on the Titanic. As that game of musical chairs picks up its tempo, to shift metaphors a bit, we can expect to see an impressive range of once-fashionable opinions and activities turned into targets for denunciation. It’s a familiar part of the process by which a waning elite assists in its own downfall.

Yet there’s another side to the story, which is that certain practices that have been scooped up by the privileged classes and used as vehicles for harmless dissidence are not necessarily as harmless as their sales pitches claim. Many of them involve risks, especially when they’re taught and practiced by people who have no clue what they’re doing. Some of those risks are relatively mild; some are anything but.

A few years back, for example, Harper’s carried an article about the downsides of mindfulness meditation, one of the most fashionable practices on the quasi-spiritual end of American pop culture. Mindfulness meditation, for those who haven’t encountered it, is a simplified (some would say bowdlerized) version of vipassana, a meditative practice developed over the last two millennia or so by Buddhist monks and nuns in south and southeast Asia. In its native habitat, it forms one part of a well-polished toolkit of methods that celibate ascetics in full-time monastic settings use, under the close observation of experienced teachers, to overcome desire and aversion -- that is to say, the basic psychological drives hardwired into the human mind -- and achieve the state of transformed awareness that mystics call enlightenment.

In that setting, it’s very effective. In today’s America, by contrast, mindfulness meditation has been ripped out of its original context, turned into a nonchemical tranquilizer, and marketed to the comfortable classes as a harmless means of relaxation, which it certainly is not. People who have no previous experience with meditation are being invited to week-long intensives where they spend every waking hour practicing this method. In most cases no effort is made to screen attendees for potential psychological problems or to warn people of the dangers of intensive spiritual work, and the people who are conducting these intensives have not gone through the kind of rigorous training and screening that any self-respecting Buddhist monastery demands of a candidate abbot.The result, as you would expect, is a bumper crop of psychiatric casualties.

The Harper’s article I mentioned above is about one of those casualties; you can read it here. It’s a classic example of the sort of yellow journalism that’s so fashionable these days -- high on shrill rhetoric of the oh-the-poor-victim variety and low on nuance, balance, and objectivity -- but it’s worth reading, because the point it makes is one that a lot of people have been desperately trying to avoid in recent years: spiritual practices are not necessarily safe. If they’re taught by people who don’t know what they’re doing, and practiced by people who haven’t had the necessary training and preparation, they can wreck you.

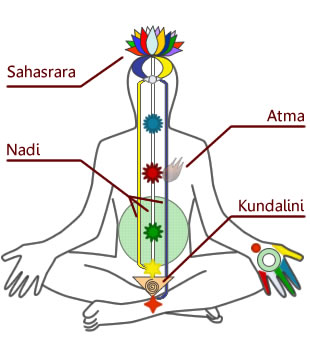

If anything, we’re fortunate that it was mindfulness meditation rather than some other spiritual practice that caught the fancy of the privileged classes. Manly P. Hall, one of the 20th century’s most respected teachers of Western occultism, described in one of his books what happened when a group of enthusiastic young men in the California occult scene decided to try kundalini yoga on their own. Kundalini yoga? Those who don’t track the details of Asian spirituality may not know that it’s a system of practices meant to set off complex electrochemical reactions in the central nervous system and the endocrine glands, getting you to the state of enlightenment much more quickly than less drastic methods can manage.

Yes, that’s as risky as it sounds. Done properly, in the proper context, it can result in enlightenment in a hurry. Done incautiously, without adequate day-by-day supervision by competent teachers, the results can be disastrous -- and in the case Hall described, they were. One after another, the young men turned pale, weak, and emaciated, and died. Kundalini yoga can do that to you. Gopi Krishna, who underwent a spontaneous experience of the same kind and wrote a classic book about it, had to spend a couple of years on strict bed rest before he recovered enough to resume ordinary daily activities. Not everyone is so lucky.

Does this mean that nobody should ever attempt to make use of traditional spiritual practices? Of course not. It means that such practices need to be performed with the same kind of care you would use when handling high-voltage electricity. It means that when the traditional teachings say “don’t do this,” you should listen, and when they say “do this before you try that,” you should listen then, too. Finally, when someone insists to you that some spiritual practice of other that used to be practiced exclusively in monasteries is a harmless means of relaxation, and that you ought to attend a week-long intensive even if you have no previous experience with meditation because nothing can possibly go wrong -- well, I hope I’ve made my point.

I want to talk a little more about this last issue, because it’s something I deal with all the time as a teacher of Western occult spirituality. The odd assortment of Western alternative spiritual traditions that got lumped together under the label of “occultism” (literally “hidden-ism” -- the word “occult” means “hidden,” as when the Moon occults a star or you have occult blood in your stools) has been powerfully shaped by its history, and one of the most significant results of that history is that we haven’t had the option of sending tens of thousands of aspirants to monasteries where they could spend all their waking hours doing spiritual practices. That option was closed off partly by the need to evade recurrent waves of violent persecution, but partly also because it’s been a couple of thousand years since we’ve had the institutional or popular support necessary to build and fund monasteries.

As a result, occultists by and large have jobs and families; they have to earn their livings and deal with the daily routine like everyone else. That means that they have to make use of spiritual practices that don’t get in the way of everyday life. Disciplines that require too much time or demand too much expenditure are out; so, even more importantly, are practices that render the practitioner incapable of making a living or dealing with the rest of the world. (In traditions that can afford monasteries, these are more common than you may think. Most monasteries, no matter what kind, have their quota of psychospiritual basket cases, who can still function only because the monastic rule tells them what to do with every minute of their time -- and the abbot can always assign someone to take care of them when they come completely unglued.)

As a result, the spiritual malpractice that too often takes place in meditation retreats and other entertainments for the well-to-do has no place in traditional Western occultism. No competent occult teacher will ever encourage anyone new to meditation to practice it every waking hour for a week. Quite the contrary, in Self-Unfoldment Through Disciplines of Realization -- his core book on spiritual training -- Manly P. Hall suggested that five minutes of meditation once a day was a good amount for complete beginners. (For what it’s worth, this is also what I recommend for those just starting out.) Meditation is like any other exercise; you have to get into shape before you try to do more than an ordinary light workout.Take someone who leads a sedentary lifestyle and tell them to run a marathon, and you can count on a bumper crop of coronaries. Doing the equivalent on the spiritual plane is no safer.

There’s another important difference between the sort of meditation that occultists practice and the sort that’s been marketed so heavily in pop culture circles, however. One of reasons that mindfulness meditation is so popular is that the simplest and most decontextualized versions of it -- which are of course the most heavily marketed of the lot -- have the effect of shutting down the thinking mind. Practitioners are taught to notice thoughts as they arise and then dismiss them, rather than thinking them, and if this is done too thoroughly -- especially in the kind of weeklong intensive workshop discussed in the Harper’s article -- the result is usually to make the thinking process freeze up altogether.

In its native habitat as a part of Buddhist monastic discipline, that isn’t a problem, because a Buddhist monk in the schools that teach vipassana is also expected to spend time every day reading the suttas -- the Buddhist scriptures -- and wrestling with the intricate metaphysical philosophy of the Abhidhamma, which is enough mental exercise to keep anyone’s brain fit. Taken out of context and taught to the inexperienced, by contrast, “mindfulness” meditation too often becomes mindlessness meditation, an off switch for the reasoning processes that can leave the mind a catatonic blank or an unsupervised playground for psychotic delusions. (The Harper’s article, for all its flaws, gives a fairly good glimpse at the results.)

That kind of mind-silencing approach has cropped up now and again in Western spirituality, too -- the technical term for it is “quietism.” Both the mainstream religions and the occult traditions have consistently and sensibly backed away from it with a reaction amounting to “Um, no.” I can’t speak for the mainstream religions, but in traditional occult philosophy the thinking mind is an essential tool for spiritual practice as well as practical existence. Shutting it down and then trying to attain higher states of consciousness is pretty much the equivalent of throwing away your hammer and saw and then trying to build a house.

That’s why the most common Western form of meditation back in the day focused on training and directing the mind rather than silencing it. The technical term for this style of meditation is discursive meditation, because it very often takes the form of a silent mental discourse or monologue. You start with a theme -- a concept, a short passage of text, or an emblem -- as a focus for your meditation. After the usual preliminaries (posture, breathing, relaxation) you bring the theme to mind, and hold it in your awareness for a time, as though looking at it. You then think about it, keeping the mind focused on the theme and the sequence of thoughts that unfold from the theme. (This takes just as much mental discipline as keeping your mind focused on a mantra or on watching thoughts arise, by the way.)

You do this for five minutes a day, to begin with, and gradually work up from there to 20 minutes a day or so. More than that? Not recommended. There are other practices, and there’s also reading and study -- just as the Buddhist monks described earlier have suttas to read and philosophy to master, Western spiritual traditions have their own texts to study and their own teachings to understand. The habit of insisting that such things don’t matter is one of the ways that people protect themselves against new ideas. Now of course reading and study won’t get you to enlightenment alone, but nobody ever said they would.

There used to be an immense literature in most Western languages on discursive meditation. Bishop Joseph Hall’s 17th-century textbook, The Art of Divine Meditation, is a classic example from within the Anglican tradition -- it’s the one I used, once I got past the very simple instructions that came with the occult study courses where I originally learned the art. There were hundreds of others. Until the late 19th century, this sort of meditation was taught to children in Sunday school as a matter of course. Over the course of the 20th century, as part of the systematic erasure of the Western world’s own inner traditions, those books were forgotten and the system they taught dropped out of common use except in a few old-fashioned occult schools -- but the system still works as well as it ever did.

Sources of themes were just as easy to come by back in the day, by the way. Those of my readers who know their way around Victorian popular literature will recall the flurry of books of meditations that appeared during that era; those were collections of themes, usually in short-essay form. The older occult traditions still have their own robust collections along the same lines, and many of them are still readily available today, even though people on the pop-culture end of occultism have generally forgotten, if they ever knew, that a great many of the most famous texts and emblems of occult tradition were designed as themes for discursive meditation, and only yield up what they have to teach when approached with that key in hand.

Outside the occult traditions, there’s an abundance of options, varying by denomination. Those of my readers who belong to the Catholic church have no doubt already thought of the stations of the Cross and the various lists of joyful mysteries, sorrowful mysteries, etc. -- good themes for discursive meditation, all of them. Those of my readers who are Protestants or Jews -- er, what did you think you were supposed to do with your scriptures, other than stare blankly at them? One of the most spiritual people I’ve ever met, an elderly woman I knew many years ago, read a chapter of the Bible every morning, meditated on it, and prayed. That was her practice, and it took her places I hope I’ll be able to reach someday.

The moral to this story is straightforward. Meditation, like any other powerful transformative process, needs to be treated with respect. If you want to follow an Asian meditative tradition, start by finding someone qualified to supervise you -- and no, the fact that a person has attended a weekend workshop or two, or works for some heavily marketed franchise or other, emphatically does not cut it. You need someone who’s been there and done that, who can tell you up front about the dangers of the practice, and will notice and help you take constructive action if something goes wrong If you prefer a Western approach to your spiritual life instead, why, I’ve already dropped some hints; follow them if you will.

And if you’re afraid of thinking, afraid of the content of your own thoughts, and are just looking for some convenient habit that will shut your mind off for a while so you can hide from the unwelcome realization that maybe you aren’t as virtuous and perfect as you like to pretend, then may I offer some advice? Try television or masturbation or drinking yourself blotto if you must, but for the gods’ sakes leave meditation alone. Cirrhosis of the liver is easier to deal with than an acute psychotic breakdown.

The flight from thinking is the covert subtext behind all the faux-Asian pseudomysticisms that have been so heavily marketed to the comfortable classes in modern America. That project has been well under way since the programmatic and meretricious volume The Gospel According To Zen first saw print back in 1970, and it’s become a massive presence in the well-paid end of alternative culture these days. Students of history know already that such projects are among the ways that waning elites assist in their own downfall, but students of history are remarkably rare among the overdeveloped world’s comfortable classes these days.

At the heart of those heavily marketed schemes, and a great deal else in today’s pop culture, is the tacit insistence that embracing the standard prejudices of your culture and your class is what enlightenment is all about. It’s understandable that the well-to-do find that notion pleasant to believe, and just as understandable that they’ve had to find ways to flee from thinking in order to maintain that delusion. Enlightenment is no respecter of persons, however, and it has even less time for the pretensions of the privileged. Those who think they are pursuing it by silencing the still, small voice of reason are all too likely to discover that while they thought they were embracing cosmic bliss, they were pitching themselves into someplace far less pleasant.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served 12 years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.

- CategoriesEdited | Asia | North America | Africa | Spiritual | Health | Culture | All Content | Front Page Stories | Commentary -- WNT Original | Analysis | Commentary | Europe

- CreatedWednesday, April 21, 2021

- Last modifiedWednesday, April 21, 2021

SUBSCRIBE

World Desk Activities

www.imf.org/en/News/Podcasts/All-Podcasts/2024/05/…

en.vedur.is/about-imo/news/volcanic-unrest-grindav…

www.sciencealert.com/shift-in-indias-vulture-popul…

Shift in India's Vulture Population Linked to Half a Million Human Deaths : ScienceAlert

A cattle painkiller introduced in the 1990s led to the unexpected crash of India's vulture populations, which still haven't recovered to their former glory.

Latest Stories

Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Digital Apartheid in Gaza: Unjust Content Moderation at the Request of Israel’s Cyber Unit July 26, 2024

- Electronic Frontier Foundation to Present Annual EFF Awards to Carolina Botero, Connecting Humanity, and 404 Media July 25, 2024

- Briefing: Negotiating States Must Address Human Rights Risks in the Proposed UN Surveillance Treaty July 24, 2024

- Journalists Sue Massachusetts TV Corporation Over Bogus YouTube Takedown Demands July 24, 2024

The Conversation

- Vale Ray Lawler: the playwright who changed the sound of Australian theatre

- Magnificent and humbling: the Paris opening ceremony was a tribute to witnessing superhuman feats of the extraordinary

- How collaboration from across Canada, and the world, is helping fight the Alberta wildfires

- Paris Olympics: Canada’s soccer drone scandal highlights the need for ethics education

The Intercept

- Honduras, 15 Years After the Coup: An Interview With Ousted President Manuel Zelaya July 26, 2024

- Google Planned to Sponsor IDF Conference That Now Denies Google Was Sponsor July 25, 2024

- Deputy Accused of Killing Sonya Massey Was Discharged From Army for Serious Misconduct July 25, 2024

- U.S. Has Never Apologized to Somali Drone Strike Victims — Even When It Admitted to Killing Civilians July 25, 2024

VTDigger

- Waterbury residents looked to FEMA buyouts after last year’s floods. They’ve heard nothing for months July 26, 2024

- At a quiet Craftsbury pond, rowers become Olympians July 26, 2024

- UVM Medical Center wins approval to buy Fanny Allen Campus July 26, 2024

- Landslides and slurries have damaged homes, roads and driveways after this month’s flood July 26, 2024

Copyright © 2024 World News Trust. All Rights Reserved.

Joomla! is Free Software released under the GNU General Public License.