June 16, 2021 (EcoSophia.net) -- The explosive growth of interest in occultism that followed the rise of the Theosophical Society in the late 19th century set many currents of thought and practice in motion, and some of those were stranger than others.

The one we’ll be exploring in this month’s adventure in America’s magical history is one of the strangest, though what makes it strange is that it was deeply rooted in the notions and prejudices of a time most people misunderstand if they think of it at all. From within the worldview of late 19th century America, it was straightforward, plausible, even obvious. It was also wrong -- but we’ll get to that.

“Just remember, son, if you touch yourself there you’ll go blind.”To make sense of the movement we’ll be discussing, it’s necessary to have some grasp of that remarkable cultural phenomena we call Victorianism. During the second half of the 19th century, throughout the English-speaking world, the great majority of educated opinion held that sex was the source of all human evil, and that sexual acts were at best filthy animal practices and at worst an infallible source of ruin that dragged not only the participants but all of society into utter degradation of body and mind. This was the era, remember, when physicians insisted in all seriousness that masturbation would cause you to sprout hair on your palms and go insane.

“Just remember, son, if you touch yourself there you’ll go blind.”To make sense of the movement we’ll be discussing, it’s necessary to have some grasp of that remarkable cultural phenomena we call Victorianism. During the second half of the 19th century, throughout the English-speaking world, the great majority of educated opinion held that sex was the source of all human evil, and that sexual acts were at best filthy animal practices and at worst an infallible source of ruin that dragged not only the participants but all of society into utter degradation of body and mind. This was the era, remember, when physicians insisted in all seriousness that masturbation would cause you to sprout hair on your palms and go insane.

That bizarre belief points straight to the source of these collective neuroses, because of course hair on the palms in traditional European folklore is the classic mark of the werewolf, the man who becomes an animal. At the root of the problem was Charles Darwin’s writings on evolution, which delivered a body blow to the self-confidence of Victorian intellectuals. Used to thinking of themselves as a little less than the angels, they suddenly found themselves only a little more than the gorillas, and the thought that they might slip the rest of the way into a purely animal existence haunted their nightmares. The werewolf, a fixture of the romantic fiction of the time, made a great metaphor for that fear; the physicians who warned young men about hairy palms probably weren’t conscious of the metaphor, which made it all the more powerful in its time.

Two of London’s tens of thousands of sex workers.Of course people still had sex. Victorian London, to judge by the available evidence, had more sex workers than any other city in Europe, and the great cities of Victorian America were almost as well provided. Read the fiction or, for that matter, the newspapers of the time and you’ll find yourself in the middle of a torrent of sexual activities wrapped up in just enough euphemisms to give them an additional jolt of prurient interest. The Victorian era was not so much a time of heightened morality as one of heightened hypocrisy or, not quite so nastily, of a vastly widened gap between the ideals people thought they should embrace and the lives they actually led. Most Victorians in the English-speaking world really did believe that sex was beastly and that a life of strict moral purity was much better; the fact that they couldn’t live up to these beliefs didn’t make the beliefs themselves any less earnestly held.

Two of London’s tens of thousands of sex workers.Of course people still had sex. Victorian London, to judge by the available evidence, had more sex workers than any other city in Europe, and the great cities of Victorian America were almost as well provided. Read the fiction or, for that matter, the newspapers of the time and you’ll find yourself in the middle of a torrent of sexual activities wrapped up in just enough euphemisms to give them an additional jolt of prurient interest. The Victorian era was not so much a time of heightened morality as one of heightened hypocrisy or, not quite so nastily, of a vastly widened gap between the ideals people thought they should embrace and the lives they actually led. Most Victorians in the English-speaking world really did believe that sex was beastly and that a life of strict moral purity was much better; the fact that they couldn’t live up to these beliefs didn’t make the beliefs themselves any less earnestly held.

One of the things that reliably happens in the presence of such a gap between ideals and reality is that people come up with ever more exalted notions of the benefits to be gained by following the ideals. That certainly happened in this case -- and that was how it happened that a significant and influential movement of prominent occultists in late 19th and early twentieth century America proclaimed that it was possible for individuals to achieve physical immortality by giving up sex and redirecting the sexual energies to the cause of endless life.

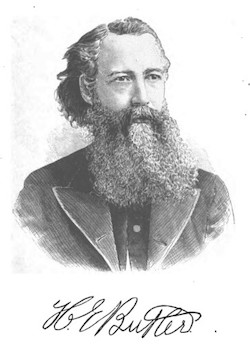

Hiram Erastus ButlerOur story begins with a man named Hiram Erastus Butler. He was born in Oneida County, New York, in 1841, grew up as an ordinary upstate New York farm boy, and joined the Union Army when the Civil War began. He wound up in a military hospital in Pennsylvania in 1863, which probably means he was wounded in the Gettysburg campaign. There he fell in love with one of the nurses, Sophia Agnes Wilson, whom he married in 1864. They had three children -- a son named Elmer and daughters named Olla Eleutheria and Sophia Agnes -- but the marriage didn’t work out, at least on Butler’s side. He bailed out on his family around 1870, leaving his wife in poverty so dire that his children spent time in a foundlings’ home.

Hiram Erastus ButlerOur story begins with a man named Hiram Erastus Butler. He was born in Oneida County, New York, in 1841, grew up as an ordinary upstate New York farm boy, and joined the Union Army when the Civil War began. He wound up in a military hospital in Pennsylvania in 1863, which probably means he was wounded in the Gettysburg campaign. There he fell in love with one of the nurses, Sophia Agnes Wilson, whom he married in 1864. They had three children -- a son named Elmer and daughters named Olla Eleutheria and Sophia Agnes -- but the marriage didn’t work out, at least on Butler’s side. He bailed out on his family around 1870, leaving his wife in poverty so dire that his children spent time in a foundlings’ home.

This isn’t what Butler claimed later. His official biography claimed that he was wounded in a sawmill accident after the war, losing several fingers, and thereafter withdrew to the New England woods and lived as a hermit for 14 years. During this time, whatever else he may or may not have been doing, he studied astrology and became a member of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, the influential occult lodge we discussed last month. He also seems to have studied the teachings of Paschal Beverly Randolph, the even more influential African-American mage we discussed last year.

Butler’s approach to the material he learned from Randolph and the H.B. of L., however, was about as far from their original focus as you can imagine. He became convinced that when the Bible said “the wages of sin is death,” it meant this literally, and -- with him as with so many Victorian thinkers -- sin, for Butler, referred to one thing and one thing only: sex. Semen, he believed, contained the essence of life, and if that essence was not lost to the body in the usual way, it could be used in advanced spiritual practices resulting in physical immortality.

In 1886, as we have seen, the H.B. of L. imploded, leaving its members in the lurch and inspiring a good many of them to find some other magical order that wasn’t the Theosophical Society. The next year Butler launched his own organization. It had the distinctly odd name Genii of Nations, Knowledge, and Religions, G.N.K.R. for short, and Butler topped this by giving himself the name “Adhy-apaka, the Hellenic Ethnomedon.” (No, I have no idea why.) He set up shop in Boston and started publishing a magazine, The Esoteric, to promote his views.

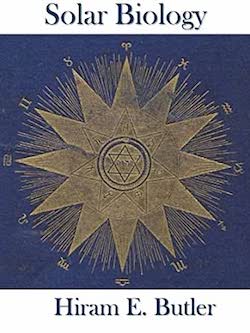

He also broke new ground in the occult book field by publishing, also in 1887, the first pop-culture astrology book. Solar Biology was the first astrology book to list astrological placements and give a paragraph of canned interpretation to each. Its long-term influence was limited by the fact that Butler used his own eccentric version of astrology, which dropped out of existence about the same time he did, but it was a bestseller in its day and plenty of other astrologers copied the idea. Modern newspaper astrology would never have happened if not for Hiram Butler. (Yes, this is just as ambivalent a form of praise as it sounds.)

He also broke new ground in the occult book field by publishing, also in 1887, the first pop-culture astrology book. Solar Biology was the first astrology book to list astrological placements and give a paragraph of canned interpretation to each. Its long-term influence was limited by the fact that Butler used his own eccentric version of astrology, which dropped out of existence about the same time he did, but it was a bestseller in its day and plenty of other astrologers copied the idea. Modern newspaper astrology would never have happened if not for Hiram Butler. (Yes, this is just as ambivalent a form of praise as it sounds.)

The appearance of the G.N.K.R. caused quite a bit of gnashing of teeth in the Theosophical Society, and it’s not hard to understand why. They’d no sooner succeeded in driving the H.B. of L. out of existence with a campaign of character assassination and innuendo, and suddenly here was another organization challenging their claim to a monopoly on occult wisdom! The response, inevitably, was the same one that the H.B. of L. got. Blavatsky herself insisted in print that the initials G.N.K.R. stood for “Gulls Nabbed by Knaves and Rascals” and assailed Butler as a brazen con artist whose spirituality was far less than skin deep. William Quan Judge, the leading American Theosophist of the era, published an equally strident piece denouncing Butler as an ignorant plagiarist.

More successful than these hit pieces, which (to be fair) were not much more extreme than the ordinary journalism of the time, were rumors that Butler and other men in his organization were engaging in immoral activities with the women who joined G.N.K.R. It’s hard to know what to make of these rumors. On the one hand, it’s unquestionably true that an organization that makes extreme claims on behalf of celibacy will attract people of both sexes who are trying to convince themselves to be celibate when all their inclinations go the other way, and this reliably results in people in such organizations following the inclinations in question more often than not. It’s also true that sex cults -- allegedly mystic orders with ornate names and symbolism, which existed for the primary purpose of giving their members a secure and congenial venue for casual sex -- were becoming a booming industry in those years. (We’ll be discussing these in much more detail later in this sequence of posts.)

Of course it’s a spiritual practice, my dear.”On the other hand, accusations of sexual immorality were a standard libel directed at alternative religious groups at that time, and were flung around freely with no regard for the facts. It’s also true that people who think they ought to be celibate but can’t quite make themselves do so tend to accuse those who are actually celibate of sharing the same weakness, and since the former category was exceedingly well stocked in Butler’s time, whipping up a moral frenzy among people who are a lot less chaste than they like to pretend in public was an easy move. So we simply don’t know whether Butler was having sex with his female students or not.

Of course it’s a spiritual practice, my dear.”On the other hand, accusations of sexual immorality were a standard libel directed at alternative religious groups at that time, and were flung around freely with no regard for the facts. It’s also true that people who think they ought to be celibate but can’t quite make themselves do so tend to accuse those who are actually celibate of sharing the same weakness, and since the former category was exceedingly well stocked in Butler’s time, whipping up a moral frenzy among people who are a lot less chaste than they like to pretend in public was an easy move. So we simply don’t know whether Butler was having sex with his female students or not.

One way or another, however, the Theosophists and the newspapers made life in Boston too hot for Butler and the G.N.K.R., and he and a group of his followers left town. They next surfaced in San Francisco, where the G.N.K.R. found new converts but ran into the same sort of trouble. In 1891, Butler did one of the other standard moves of alternative spiritual leaders in his time, moved to a rural property near Applegate in northern California, and established a commune.

A postcard from 1909 showing the Applegate commune.I gather that there are still people who think that communes were an invention of the 1960s counterculture, and I’m not too surprised, as that level of stark historical ignorance is all too common in other fields these days. In point of fact, the communes of the 1960s were a faded echo of one of the grand traditions of American alternative culture. The commune founded by Johannes Kelpius and his fellow mystics in 1694 in the trackless wilderness of eastern Pennsylvania, the subject of the first post in this sequence, was the harbinger of a vast outpouring of communes of every imaginable kind across the entire landscape of the United States.

A postcard from 1909 showing the Applegate commune.I gather that there are still people who think that communes were an invention of the 1960s counterculture, and I’m not too surprised, as that level of stark historical ignorance is all too common in other fields these days. In point of fact, the communes of the 1960s were a faded echo of one of the grand traditions of American alternative culture. The commune founded by Johannes Kelpius and his fellow mystics in 1694 in the trackless wilderness of eastern Pennsylvania, the subject of the first post in this sequence, was the harbinger of a vast outpouring of communes of every imaginable kind across the entire landscape of the United States.

Butler himself grew up near one of the most famous of these -- the Oneida commune founded by free-love prophet John Humphrey Noyes -- and there were plenty of others in America in his day, so he was following a familiar pattern. He and his followers, having retitled themselves the Esoteric Fraternity, built a big communal house on their new property, planted gardens, got a publishing house up and running to provide the steady infusion of cash that every viable commune needs, and settled in for the long haul.

The commune is still there. Butler, on the other hand, is not. He died in 1916 at the depressingly ordinary age of 75. Nor did any of his followers manage to live forever, or even exceed the normal human lifespan. They still managed to find successors, and there are still members of the organization living in the house that Hiram Butler built, but the quest for immortality through chastity passed to other hands a long time ago.

Hiram Butler’s current residence.You might be surprised, dear reader, that this quest didn’t end with Butler’s death. It did not, because occultists in those days were perfectly aware of the problems with drawing sweeping conclusions from a sample size of one. That Butler merely managed a long and healthy old age didn’t disprove his theory -- it could be the case, the occultists reasoned, that Butler had the right theory but hadn’t put it into effect the right way, or that there was some confounding factor that Butler hadn’t taken into account. The logical response was to try as many variations on the same approach as possible, and see if one of them worked. This they accordingly did.

Hiram Butler’s current residence.You might be surprised, dear reader, that this quest didn’t end with Butler’s death. It did not, because occultists in those days were perfectly aware of the problems with drawing sweeping conclusions from a sample size of one. That Butler merely managed a long and healthy old age didn’t disprove his theory -- it could be the case, the occultists reasoned, that Butler had the right theory but hadn’t put it into effect the right way, or that there was some confounding factor that Butler hadn’t taken into account. The logical response was to try as many variations on the same approach as possible, and see if one of them worked. This they accordingly did.

We could spend a long time talking about the variations on that theme that American occultists played over the course of the early twentieth century, but we’ll limit ourselves to one. This was George Washington Carey, a farm boy like Butler, born in Dixon, Illinois in 1845. When he was a year and a half old, his family did as so many other Americans were doing just then: they sold their farm, bought a covered wagon and a year’s supplies, and set out on the Oregon Trail. They settled in the Oregon Territory, and the next thing we hear about Carey, forty years had passed and he owned the general store in the dusty little frontier town of Yakima, Washington.

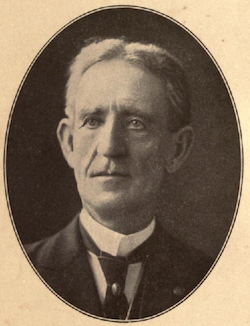

George W. CareyYakima in those days wasn’t quite a one-horse town, but it was small enough that Carey was also the postmaster, an insurance agent, and a salesman for Dr. Jordan’s Medicines, a popular brand of the era. (His wife Lucy was the town hatmaker.) Selling medicines inspired a passion for healing in Carey; he promptly became a physician, which in those days was usually done via apprenticeship, and the particular school of medicine he studied -- well, that involves complexities of its own.

George W. CareyYakima in those days wasn’t quite a one-horse town, but it was small enough that Carey was also the postmaster, an insurance agent, and a salesman for Dr. Jordan’s Medicines, a popular brand of the era. (His wife Lucy was the town hatmaker.) Selling medicines inspired a passion for healing in Carey; he promptly became a physician, which in those days was usually done via apprenticeship, and the particular school of medicine he studied -- well, that involves complexities of its own.

In Carey’s time there were many approaches to medicine. The one that’s officially approved these days was only one, and, before the invention of antibiotics, it wasn’t noticeably more successful than the others. Herbal medicine was common, and so was homeopathic medicine -- if you haven’t encountered this, it’s a system that uses specially prepared microdoses of medicines to goose the body’s systems into balance. Another was called biochemic medicine. It was an offshoot of homeopathy created by a German doctor, Dr. W.H. Schüssler, who noted that human bodies normally heal themselves of illnesses and injuries, and decided to experiment with the mineral salts found in the human body itself. 19th-century science had detected twelve of these, and he found that microdoses of these salts prepared in the usual homeopathic way could be used to treat most diseases with good results.

That was the system of medicine that Carey studied. He became a capable biochemic doctor and an enthusiastic promoter of the system, and founded a College of Biochemistry in Yakima with several other local physicians, though it doesn’t seem to have lasted long. In 1894 he published The Biochemic System of Medicine, a good solid textbook on the system, which remains in print to this day -- but after that, another gap in the records closes in, and his peregrinations for the next two decades remain obscure.

The curtain rises again in 1917. By that year Carey had relocated to southern California -- Lucy was apparently no longer with him, though the details are unknown. (Given his age, she may well have died by then.) He was still a passionate supporter of biochemic medicine, but somewhere in there he had encountered the ideas of Hiram E. Butler, and became convinced that he had discovered the secret for which Butler had sought in vain. A life free of sex and alcohol was essential for physical immortality, he taught, but it was not enough by itself: the next step required biochemic medicines.

The curtain rises again in 1917. By that year Carey had relocated to southern California -- Lucy was apparently no longer with him, though the details are unknown. (Given his age, she may well have died by then.) He was still a passionate supporter of biochemic medicine, but somewhere in there he had encountered the ideas of Hiram E. Butler, and became convinced that he had discovered the secret for which Butler had sought in vain. A life free of sex and alcohol was essential for physical immortality, he taught, but it was not enough by itself: the next step required biochemic medicines.

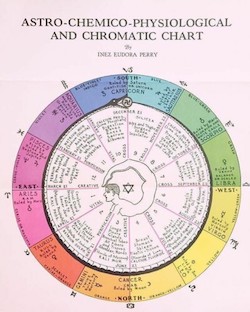

Carey had by this time become a capable astrologer, and he worked out a table correlating each of the twelve biochemic cell salts to a sign of the zodiac. Drawing on a free mix of offbeat Bible interpretation, occult teaching, and his own considerable knowlege of anatomy, he argued that doses of the right combination of cell salts -- which varied from person to person based on birth date -- would affect the sympathetic nervous system and the pineal gland, setting off a cascade of transformations that would eventually result in physical immortality. He taught this system to students in his own school in Los Angeles, and he also published a series of impressively weird books, beginning with The Tree of Life in 1917 and ending with God-Man: The Word Made Flesh in 1920, setting out his system of personal transformation.

That system became a standard part of the curriculum of dozens of occult schools and magical lodges in early twentieth century America, and you can find people still teaching it today. Carey is, I am sorry to say, not one of them. He died in 1924, at the ripe but still rather ordinary age of 79. The regimen of birth date-linked cell salts he devised has a variety of positive effects on body and mind, but it isn’t the key to immortality. He wasn’t the last American occultist to preach bodily immortality and then spoil it all by dying -- that honor belongs to Paul Foster Case, whom we’ll be discussing in a later post -- but after Carey’s time, promoters of immortality had to contend with growing skepticism within the occult community.

That system became a standard part of the curriculum of dozens of occult schools and magical lodges in early twentieth century America, and you can find people still teaching it today. Carey is, I am sorry to say, not one of them. He died in 1924, at the ripe but still rather ordinary age of 79. The regimen of birth date-linked cell salts he devised has a variety of positive effects on body and mind, but it isn’t the key to immortality. He wasn’t the last American occultist to preach bodily immortality and then spoil it all by dying -- that honor belongs to Paul Foster Case, whom we’ll be discussing in a later post -- but after Carey’s time, promoters of immortality had to contend with growing skepticism within the occult community.

Occultists aren’t supposed to behave like that, according to the standard rationalist rhetoric these days. They aren’t supposed to test hypotheses against the evidence from experiments and make up their own minds on that basis. Apparently no one told the American occult community this in Butler’s time, or Carey’s, or Case’s, because that’s exactly what they did. From within the worldview of Victorian culture, as modified by the occult revival of the early Theosophical era, Hiram Butler’s theory about physical immortality was a hypothesis worth investigating, and he and a great many other students of the occult proceeded to investigate it.

The result of their research was that Butler’s theory was disproven and discarded. As scientists know -- well, the honest ones, at least -- that’s a necessary and appropriate step in the growth of any body of systematic knowledge. Early twentieth century American occultism was gathering just such a body of knowledge, testing the traditional lore it had received from European occultism and the legacies of earlier generations of American occultists, and assembling a toolkit of approaches to personal transformation that was broadly shared among the various schools, orders, and societies of the movement.

That process involved a certain amount of discarded hypotheses, of the kind we’ve just followed. It also involved some exceedingly colorful squabbles between contending occultists. We’ll talk about one of the most colorful of those -- the wars between America’s Rosicrucian orders -- in next month’s installment in this sequence.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served twelve years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.