June 30, 2021 (EcoSophia.net) -- One of the things I find fascinating about the deepening twilight of industrial society is how rigid our modern notions of technology have become.

Most people these days, asked to imagine a society with technology about as advanced as ours, present something all but identical to what we’ve got now; asked to imagine a society with less advanced technology, they spring to a distorted pop-culture version of early medieval Europe if they don’t leap straight to even more distorted pop-culture notions about the Stone Age; asked to imagine a society with technology more advanced than ours, you can bet dollars for dilithium crystals that they’ll rehash the same tired imagery from early 20th-century sci-fi that has been stuck sideways in our collective imagination for decades now.

It’s not gonna happen. Deal.All this can be amusing, granted, but it makes for unnecessary confusion when someone like me attempts to talk about the future of industrial society in terms that don’t fit that absurdly rigid scheme. Over and over again, for example, people find out that I don’t believe that industrial society is headed onward and upward to the stars, and once they get past the slackjawed reaction this reliably fields -- what do you mean the Great God Progress won’t grant us the Star Trek future of our dreams? -- they assume that I think we’re headed back to the Middle Ages,.

It’s not gonna happen. Deal.All this can be amusing, granted, but it makes for unnecessary confusion when someone like me attempts to talk about the future of industrial society in terms that don’t fit that absurdly rigid scheme. Over and over again, for example, people find out that I don’t believe that industrial society is headed onward and upward to the stars, and once they get past the slackjawed reaction this reliably fields -- what do you mean the Great God Progress won’t grant us the Star Trek future of our dreams? -- they assume that I think we’re headed back to the Middle Ages,.

That’s not even remotely true, of course. I’ve written nonfiction books -- The Ecotechnic Future and Dark Age America in particular -- explaining what I expect deindustrial society to look like, at least for the half a millennium or so until the decline ends and the cultures that will build on our ruins begin to rise. I’ve also written a science fiction novel, Star’s Reach, set in America’s deindustrial dark ages circa 2485 AD, and if you can confuse the setting in which Trey sunna Gwen and his companions go looking for messages from space with any part of the European Middle Ages, all I can say is you probably need new glasses. Yet I still get people making that same assumption about my views every few months, and now that the price of oil is climbing steadily again and we’ve got a serious energy crisis on its way, I expect to encounter it even more regularly for a while.

Behind this curious rigidity of the imagination is the faith in progress I lampooned above, the really rather bizarre notion that human history is a predestined one-way journey from the caves to the stars and we occupy the most important position in that journey, the inflection point where the leap into infinity is about to start. Woven into that faith-based belief system is the implicit claim that the kind of technology we’ve got right now is the only kind of technology that matters, that the technology of the future will be like ours raised to the power of infinity, and that people in past civilizations trudged through a hopeless round of misery and poverty because nobody had gotten around to inventing our kind of technology yet. In this way of thinking, every cultural and technological phenomenon of past and present is judged on the basis of how well it falls in with our current ideas about what will further the grand march of humanity toward its supposedly predestined future among the stars.

“What do you mean we’re not the wave of the future?”There’s a useful term for this kind of thinking in the history of ideas: Whig history. Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, you see, the Whigs -- their official name was the Liberal Party, but next to no one called them that -- had a dominant role in British intellectual culture. Historians who shared the views of the Whig consensus believed devoutly that 18th- and 19th-century British liberalism was the wave of the future, so that every cultural phenomenon of the past could be judged by how much it contributed to the eventual triumph of Whig opinions, and that’s how they wrote their histories. I don’t imagine it ever occurred to them that the Liberal Party would fall from power in the early 20th century, and eventually end up so small and marginal that it would have to merge with another fringe group to make today’s Liberal Democratic Party. It’s astonishing how many people who think of their own ideas as the wave of the future never get around to noticing that every wave eventually breaks and rolls back out to sea.

“What do you mean we’re not the wave of the future?”There’s a useful term for this kind of thinking in the history of ideas: Whig history. Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, you see, the Whigs -- their official name was the Liberal Party, but next to no one called them that -- had a dominant role in British intellectual culture. Historians who shared the views of the Whig consensus believed devoutly that 18th- and 19th-century British liberalism was the wave of the future, so that every cultural phenomenon of the past could be judged by how much it contributed to the eventual triumph of Whig opinions, and that’s how they wrote their histories. I don’t imagine it ever occurred to them that the Liberal Party would fall from power in the early 20th century, and eventually end up so small and marginal that it would have to merge with another fringe group to make today’s Liberal Democratic Party. It’s astonishing how many people who think of their own ideas as the wave of the future never get around to noticing that every wave eventually breaks and rolls back out to sea.

Whig history is pandemic in our thinking about technology these days. This is why Kim Stanley Robinson’s otherwise fine novel The Years of Rice and Salt -- which imagines a parallel history in which Europe was conquered by the Turks -- assumes as a matter of course that other societies would get around to evolving exactly the same suite of advanced technologies that Europe did. It’s why Neal Stephenson’s equally good novel Anathem, which is set on a parallel world some thousands of years in the equivalent of our future, nonetheless has characters wearing tee shirts, eating energy bars, and accessing the internet through smartphones.

Straight lines to infinity: it’s what we do.It apparently did not occur to either of these gifted writers that technologies are profoundly shaped by cultural factors, and that European civilization put its efforts and resources into a specific suite of technological projects for its own idiosyncratic reasons. They don’t seem to have considered the likelihood that other cultures that developed technic civilizations -- that is, civilizations that get a large proportion of their energy from sources other than muscle and biomass -- might apply their efforts and resources to entirely different projects, and thus create entirely different technological suites. The drive toward infinite distance that made European civilization the only culture in recorded history to use linear perspective in its art, after all, also expresses itself in the whole trajectory of our technology, from the firearms and sailing vessels that launched Europe on its career of global conquest right up to the spacecraft and Internet of today. Other civilizations have other interests.

Straight lines to infinity: it’s what we do.It apparently did not occur to either of these gifted writers that technologies are profoundly shaped by cultural factors, and that European civilization put its efforts and resources into a specific suite of technological projects for its own idiosyncratic reasons. They don’t seem to have considered the likelihood that other cultures that developed technic civilizations -- that is, civilizations that get a large proportion of their energy from sources other than muscle and biomass -- might apply their efforts and resources to entirely different projects, and thus create entirely different technological suites. The drive toward infinite distance that made European civilization the only culture in recorded history to use linear perspective in its art, after all, also expresses itself in the whole trajectory of our technology, from the firearms and sailing vessels that launched Europe on its career of global conquest right up to the spacecraft and Internet of today. Other civilizations have other interests.

There are plenty of reasons why it’s a good idea to try to get past the current iteration of Whig history and try to see the possibilities of technology in a less blinkered fashion. One of them, the one I want to discuss in this week’s post, is the suggestion that civilizations in prehistory might have had advanced technologies -- as advanced as ours, perhaps, or even more so.

That suggestion has been circulated in the occult community for a very long time: since the late 19th century, certainly, when a number of occult schools inserted discussions of the civilizations of the distant past into their teachings. In the particular schools in which I had my training, the idea was that ours is the fifth cycle of hominid civilizations on Earth. The four previous cycles are called the Polarian, Hyperborean, Lemurian, and Atlantean ages, though these are purely conventional labels, borrowed from geology and legend to provide convenient monikers for these phases of the past. What the peoples of these distant times called themselves and their nations, or even what languages they spoke, nobody claims to know.

To judge from the scraps of traditional lore, the Polarian and Hyperborean cycles took place during the last interglacial, the period before the last ice age when global temperatures were considerably higher than they are now, and human civilization in these eras centered on the regions, then ice-free and temperate in climate, around the Earth’s north pole. The Lemurian and Atlantean cycles took place during the last ice age, when sea levels were much lower than they are today. The center of human civilization in the Lemurian cycle was the now-submerged land mass that today’s geologists call Sundaland, a subcontinent the size of India of which today’s island chains between southeast Asia and Australia were the mountain regions. The centers of human civilization in the Atlantean cycle were a variety of island regions around the Atlantic basin that went under when the ice age ended.

Not quite a lost continent.All of this has of course been roundly rejected by scientific opinion for a very long time. In recent years, mind you, that rejection has begun to waver. A good many paleoanthropologists these days, for example, are willing to consider the possibility that Sundaland was a major center of human culture in very ancient times, the source from which several language families and certain important cultural innovations spread to other parts of the world. For that matter, the Dogger Bank -- one of those now-drowned islands I mentioned a moment ago -- is being studied by archeologists as a significant center of human culture back in the days when the seas were so low that you could walk from France to Ireland without ever getting your feet wet.

Not quite a lost continent.All of this has of course been roundly rejected by scientific opinion for a very long time. In recent years, mind you, that rejection has begun to waver. A good many paleoanthropologists these days, for example, are willing to consider the possibility that Sundaland was a major center of human culture in very ancient times, the source from which several language families and certain important cultural innovations spread to other parts of the world. For that matter, the Dogger Bank -- one of those now-drowned islands I mentioned a moment ago -- is being studied by archeologists as a significant center of human culture back in the days when the seas were so low that you could walk from France to Ireland without ever getting your feet wet.

Yet the one possibility nobody in the cultural mainstram is willing to discuss, for fear of sacrificing their respectability once and for all, is the idea that civilizations in these ancient times might have had relatively advanced technology. That flies in the face of the mythology of progress mentioned earlier. If technic civilizations have risen and fallen before, how can we cling to the fantasy that we are destiny’s darlings, fated to follow our own culture’s obsession with infinite distance out to some Buck Rogers destiny out there among the stars?

Of course there’s more to it than that. We can be sure that no previous technic civilization during the last few million years extracted any significant amount of coal or oil from the Earth. We know this because when people started digging for coal and drilling for oil in our cycle, they found lots of it in easily accessible deposits close to the surface. Any civilization that comes after ours won’t have that sort of luck waiting for them, since we’ve already mined and drilled every easily accessible deposit of all the fossil fuels and are currently going to extreme lengths to get the rest of them too. We can also be sure that no previous hominid civilization dug deep mines the way we do -- the traces would be impossible to miss -- and if they put up satellites, those went into low earth orbit only, because the time it takes for satellites to fall out of middle and high orbits is long enough that some of them would still be up there, visible on our radar screens.

What this means, of course, is that no previous technic civilization in the last few million years has had the identical kind of advanced technology that ours has developed. This doesn’t mean that there have been no previous technic civilizations on this planet in the last few million years, or that they didn’t have some other kind of technology, radically different from ours. It does place serious challenges in the way of trying to determine if there were any such technic cultures. How do you look for something when you only have one idiosyncratic sample to go by, and can be sure from the evidence that any others didn’t follow the same pattern as that sample?

You look for anomalies. You look for things that can’t be done using any of the technological suites available to pre-technic societies, but were done anyway -- and this is where we catch the glint of pale metal in an ancient tomb.

Solid aluminum belt fittings from a Dark Age grave in Nanjing.There are countless thousands of burial mounds in China tempting archeologists. One of them near Nanjing was excavated in the 1950s. It was the tomb of a nobleman from the Jin dynasty, one of the short-lived Dark Age regimes that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty, China’s equivalent of the Roman Empire. The contents of the tomb were pretty normal, right down to a belt on the deceased decorated with metal plates. The one curious detail was that some of the plates on the belt were made of nearly pure aluminum.

Solid aluminum belt fittings from a Dark Age grave in Nanjing.There are countless thousands of burial mounds in China tempting archeologists. One of them near Nanjing was excavated in the 1950s. It was the tomb of a nobleman from the Jin dynasty, one of the short-lived Dark Age regimes that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty, China’s equivalent of the Roman Empire. The contents of the tomb were pretty normal, right down to a belt on the deceased decorated with metal plates. The one curious detail was that some of the plates on the belt were made of nearly pure aluminum.

We don’t think much of aluminum these days; it’s cheap, abundant, and flimsy. Until scientists figured out the trick of using electricity to smelt it from bauxite in the early 20th century, however, it was one of the rarest metals on earth. For reasons that make perfect sense if you happen to be a physicist, extracting aluminum from its ores is astoundingly difficult. When the Washington Monument in Washington DC was completed in the late 19th century, it was topped off with a point of pure aluminum: a triumph of modern science at the time.

So how did pieces of aluminum end up in a dark age tomb in China? Nobody knows. Scientists have not exactly been eager to find out. The most often cited paper on the subject these days is a triumph of circular reasoning: it argues -- and no, I’m not making this up -- that since we know the Chinese didn’t have the technology to smelt aluminum, the belt plates couldn’t have been found in the tomb. QED!

It’s one of the most basic rules of logic that if something has actually happened, it has to be possible. Apparently the authors of this paper were asleep in class the day that was discussed. Once extracted from ore, aluminum is very easy to melt, cast, and work, and so all we know from the existence of those pieces of aluminum is that someone, at some point before the rise of the Jin dynasty, figured out how to make some. The aluminum might have been very old by the time it was turned into decor for a dark age warlord. It’s an anomaly, of the kind that might point to the existence of a technic society in the distant past.

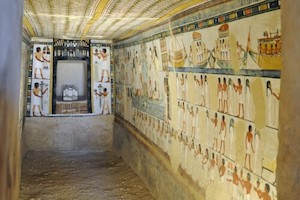

Notice the gorgeous paintings on the ceiling, untouched by soot.There are others. One of the most intriguing consists of something that isn’t there. Think of all those Egyptian tombs that were excavated in solid rock, often very far down where no light from the entrance will reach. All of them are carved and painted, a process that would have taken many hours in decent light. In most tombs there is no trace of soot on the ceiling, and soot, of course, is what you get from lamps, candles, torches -- any pre-technic source of light. How did the artists get light down there to work by? Nobody knows. Claims have been made concerning mirrors, but polished brass -- the standard mirror stock available back then -- doesn’t reflect much light. It’s another anomaly, another hint that something unexpected might have been in use.

Notice the gorgeous paintings on the ceiling, untouched by soot.There are others. One of the most intriguing consists of something that isn’t there. Think of all those Egyptian tombs that were excavated in solid rock, often very far down where no light from the entrance will reach. All of them are carved and painted, a process that would have taken many hours in decent light. In most tombs there is no trace of soot on the ceiling, and soot, of course, is what you get from lamps, candles, torches -- any pre-technic source of light. How did the artists get light down there to work by? Nobody knows. Claims have been made concerning mirrors, but polished brass -- the standard mirror stock available back then -- doesn’t reflect much light. It’s another anomaly, another hint that something unexpected might have been in use.

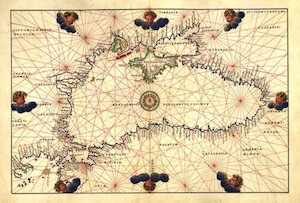

Then there are the maps. For some reason when people start talking about anomalous maps -- and there are a lot of those -- discussion almost always focused on the Piri Re’is map, a map made by a Turkish admiral in the early 16th century that probably includes some information picked up from the voyages of Christopher Columbus. Some people claim that it also has information that nobody in sixteenth century Turkey could have had, but the jury’s out on that one. I mention this here because if you try to insist I’m talking about the Piri Re’is map, I’m going to make fun of you and then not let you reply. Got it? You were warned.

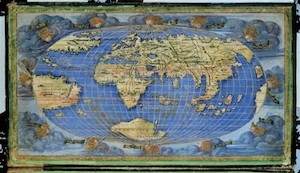

The Roselli map, painted before 1527. Notice the continent south of Africa.I’m not talking about the Piri Re’is map. I’m talking about two other sets of maps that are considerably more interesting. The first is an assortment of maps from the European Renaissance that show, very clearly, the continent of Antarctica. Officially Antarctica wasn’t discovered until centuries later and nobody knew what shape it was until the 19th century. Still, there it is, portrayed in maps from long before then, with the correct general shape. These maps generally got the scale wrong, but then they also quite often got the scale of India, Africa, and Scotland wrong; mapmaking was an inexact art in those days.

The Roselli map, painted before 1527. Notice the continent south of Africa.I’m not talking about the Piri Re’is map. I’m talking about two other sets of maps that are considerably more interesting. The first is an assortment of maps from the European Renaissance that show, very clearly, the continent of Antarctica. Officially Antarctica wasn’t discovered until centuries later and nobody knew what shape it was until the 19th century. Still, there it is, portrayed in maps from long before then, with the correct general shape. These maps generally got the scale wrong, but then they also quite often got the scale of India, Africa, and Scotland wrong; mapmaking was an inexact art in those days.

The official line regarding these maps is even funnier than the one regarding those aluminum belt plates. The claim is that mapmakers in the Renaissance put an extra continent at the south pole because they thought it made the world look more symmetrical. No, nobody cites a letter from one of the mapmakers saying this; it’s pure handwaving, designed to distract attention from something that chucks our fantasies of being destiny’s darlings into the trash where they belong.

Those aren’t the most interesting of the anomalous maps, however. That title belongs to the portolan charts, which are maps of the Mediterranean that appeared sometime around 1300. They all appear to be direct or indirect copies of the same original chart. They are accurate to a degree no mapmaker in 1300 could match, nor is there any evidence that mapmakers in Greek or Roman times could have produced them. In particular, they get the longitude of the lands around the Mediterranean right, or nearly right, to a degree nobody on Earth managed until the invention of accurate chronometers in the 19th century. Yet there they are, demonstrating that someone had geographic and cartographic knowledge that no known civilization had until modern times.

A portolan chart of the Black Sea. You can still sail by them, and get to your port.Nobody knows how the information behind these maps got into the hands of medieval and Renaissance cartographers. Speculations about what might have been found in Constantinople when it fell to the Turks in 1453, or what might have been kept at the library of Alexandria before it was looted and burnt many centuries before, are just that, speculations. All we have are anomalies like the ones I’ve just listed, details that don’t fit the preferred modern take on history, whispers from antiquity that suggest that maybe, just maybe, history is not the straight line we like to think it is.

A portolan chart of the Black Sea. You can still sail by them, and get to your port.Nobody knows how the information behind these maps got into the hands of medieval and Renaissance cartographers. Speculations about what might have been found in Constantinople when it fell to the Turks in 1453, or what might have been kept at the library of Alexandria before it was looted and burnt many centuries before, are just that, speculations. All we have are anomalies like the ones I’ve just listed, details that don’t fit the preferred modern take on history, whispers from antiquity that suggest that maybe, just maybe, history is not the straight line we like to think it is.

None of this proves the existence of advanced civilizations in prehistory. All it does is show that traces of the kind we would expect to see from lost technic civilizations of the very distant past are in fact to be found. It’s possible to make a few speculations about the technologies that one or more of those civilizations must have had; the presence of aluminum suggests that they knew how to produce electricity, and scraps of surviving electrical technology, perhaps preserved as a secret of the temple priesthoods, might also explain those soot-free tombs in Egypt. The details on the maps are hard to explain unless some ancient civilization had a maritime technology that could do the same thing as its equivalent in late nineteenth century Europe. Beyond this, for the moment, it’s impossible to go.

All this is worth keeping in mind, of course, for reasons that go beyond the strictly historical. Modern industrial civilization is well into the familiar course of decline and fall. Look out the window at the decaying infrastructure, the shredding social fabric, and the destabilized environment, and you’re seeing what people in all those other falling civilizations saw from their windows in their own times. If the occult teachings I learned are correct, this isn’t the end of the present cycle of civilizations -- there are supposed to be several more great civilizations before the current cycle comes to an end -- but we’re past the peak, and what remains of our civilization and the two to come will go through their own shorter cycles in the course of a greater decline. After that? There are supposed to be two more cycles of civilization, separated from ours and each other by long intervals of tribal existence, before humanity finishes its time on this planet.

Right now, however, the decline and fall of the industrial age is understandably on the minds of many people. As we run face first into the coming energy crisis, it will be on the minds of many more. A little reflection about what kind of whispers from antiquity we might be able to offer to the successor cultures that will come after us may not be misplaced.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served twelve years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.