Dec. 29, 2021 (EcoSophia.net) -- It’s been more or less standard practice on this blog for a while now that, whenever there are five Wednesdays in a month, I ask my readers what they want to hear about, and write an essay on that subject for the fifth Wednesday’s post.

That’s resulted in some of the stranger essays I’ve published here. Readers who don’t know their way around the lingo of classic Western occultism may well have suspected, the moment they saw the title of today’s post, that it was going to be another addition to that list. Those who are literate in that admittedly exotic jargon -- well, they didn’t have to guess.

By that term “classic Western occultism,” by the way, I mean the great synthesis of occult thought that emerged in the 19th century, as scholars and occult practitioners revived the magical traditions of the Renaissance and reinterpreted those and older teachings with an eye toward modern science and the spiritual traditions of Asia. From its birth in 1854, with the publication of the first volume of Eliphas Levi’s Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic, to its gradual eclipse in the last decades of the 20th century, classic Western occultism gave rise to an extraordinarily rich and diverse body of spiritual teachings.

There is no universally accepted orthodoxy in those teachings, though the followers of certain writers have now and then tried to create one; there is, rather, a broad consensus whch admits of endless variations. Those of my readers who know their way around the religious dimensions of the ancient world will probably already have thought of Gnosticism, and the comparison’s a valid one: the old Gnostics didn’t have an orthodoxy, either, and the narratives included in collections such as the Nag Hammadi library are just as diverse and creative as the narratives of classic Western occultism.

It’s one of the things that happens quite reliably when the religious traditions of a civilization fall victim to rigor mortis, and people start to turn to the quest for personal experience of the inner realms of being as a replacement for blind faith in someone else’s visions.

It was within classic Western occultism that Lemuria first became a familiar presence in modern times. I’m not sure how many people realize these days, however, that Lemuria started out its strange career as a scientific hypothesis, not an occult teaching.

It was within classic Western occultism that Lemuria first became a familiar presence in modern times. I’m not sure how many people realize these days, however, that Lemuria started out its strange career as a scientific hypothesis, not an occult teaching.

It was first proposed in 1864 by British zoologist Philip Sclater to explain an anomaly in the fossil record. Lemurs, those archaic primates now found only on the island of Madagascar,, had also been found in fossil form in southern India.

In those days continental drift hadn’t even been theorized yet -- it spent half a century being dismissed as crackpot pseudoscience by the scientific establishment once Alfred Wegener got around to proposing it, but that’s another story. So the only option Sclater could come up with to explain those lemur fossils was a land bridge that must long ago have connected India with the eastern shores of Africa.

If you’ll look at a globe or a world map, you’ll find that a line drawn from southern India to eastern Africa cuts across the western half or so of the Indian Ocean. Something odd happened, however, when occultists started talking about Lemuria, which they did in the 1870s.

They placed it much further east, roughly where the islands off Southeast Asia are today. They didn’t limit its occupants to lemurs, either.

According to the visionary accounts collected by occultists in that era, Lemuria had been an important center of human culture in an age long before the rise of Atlantis. Its people rose to a relatively high level of civilization in those distant times, and spread colonies and cultural influences across much of the world.

Thereafter natural disasters caused their homeland to be drowned beneath the ocean, and a long and troubled era followed before the dawn of the Atlantean age millennia later.

Of course these claims were dismissed out of hand by the scientific establishment of the time. What makes this dismissal especially interesting is that research during the last few decades has shown that in broad outline, the occultists were right.

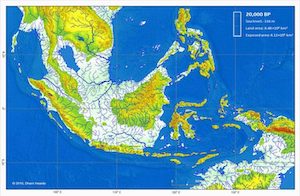

There was a land mass south and east of Southeast Asia, a subcontinent the size of India, whose mountain ranges now form island chains in that region of the world. Geologists nowadays call it Sundaland.

It was above water at the height of the last Ice Age, when most of today’s temperate zones were frozen tundra or vast wastelands of glacial ice; it was inhabited by human beings, and it seems to have been the place from which at least one language family and several important early technological innovations spread through the rest of the Old World. So some unexpected scraps of actual knowledge seem to have found their way to occultists back in the day.

Sundaland 20,000 years ago.Mind you, that doesn’t mean that everything you’ll read about Lemuria in occult sources from the classic era of Western occultism is worth taking seriously. One of the great mistakes made by the occultists of that time -- a mistake that was enthusiastically cheered on by some of the leading figures in the movement, and is still being perpetuated in certain incautious circles today -- was overconfidence in the factual accuracy of material drawn from visionary sources.

Sundaland 20,000 years ago.Mind you, that doesn’t mean that everything you’ll read about Lemuria in occult sources from the classic era of Western occultism is worth taking seriously. One of the great mistakes made by the occultists of that time -- a mistake that was enthusiastically cheered on by some of the leading figures in the movement, and is still being perpetuated in certain incautious circles today -- was overconfidence in the factual accuracy of material drawn from visionary sources.

A great deal of material about the Lemurian era and the rest of our species’ distant past was obtained through what occultists then called clairvoyance and their avant-garde heirs today call remote viewing. Can you get accurate information that way? Sometimes, yes, or so the evidence suggests, but what you get is inevitably jumbled up with stray imagery from a galaxy of internal and external sources, and has to be assessed with great care.

This wasn’t something that leading occultists at the time were willing to concede. The crisis of philosophy I discussed two weeks ago was an explosive issue in the late 19th and early 20th century. The thought that seership could be used to do an end run around the limits to human knowledge Kant had traced out was very tempting to enthusiastic thinkers at that time.

Unfortunately those limits apply just as forcefully to clairvoyance or, shall we say, imaginative consciousness, as they do to every other mode of human experience. That was how we ended up with giddy accounts of Lemurian prehistory in which hermaphroditic, egg-laying Lemurians walked pet plesiosaurs on leashes through an atmosphere composed of “fire-mist,” and a great many other claims about the Lemurian age that sounded plausible a century ago but look pretty daft in the light of more recent knowledge.

The moral to this story? Human psychism, like human reason and the human senses, is anything but infallible, and needs to be tested against other sources of evidence to determine just what kind of sense to make of it.

What makes the old occult teaching about Lemuria worth taking seriously as something more than a symbolic narrative is that it meshes surprisingly well with evidence from other sources, such as historical linguistics and paleoclimatology. What makes those plesiosaurs on leashes, fire-mist atmospheres, and some of the other oddities of occult Lemuriology less useful outside the realm of symbolism is that other sources of evidence contradict them.

All this should be kept in mind as we turn to the Lemurian deviation.

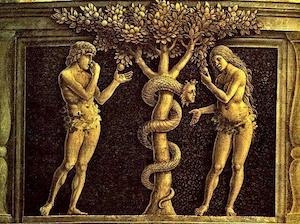

We can start with the narrative of the Fall of Humanity laid out in the third chapter of the Book of Genesis: the story of Adam, Eve, the serpent, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and the rest of it. These days, as far as I can tell, most people either take that story literally or reject it completely.

The occultists of the classic era did neither. They agreed with the atheists that the whole business of talking snakes and magic apples could not be taken seriously as a literal description of what happened -- but they agreed with the orthodox that something had happened. There was an event corresponding to the legend, and the memory of that event was passed down through countless generations in the form of a colorful folktale.

A colorful folktale.The occultists noted that stories of a drastic misstep somewhere far back in humanity’s past, an event that in some sense brought death and suffering into the world, are tolerably widespread in the myths of ancient peoples: the story of Pandora’s box is one example that’s well known to most people these days.

A colorful folktale.The occultists noted that stories of a drastic misstep somewhere far back in humanity’s past, an event that in some sense brought death and suffering into the world, are tolerably widespread in the myths of ancient peoples: the story of Pandora’s box is one example that’s well known to most people these days.

They argued that the early narratives of the Bible generally should be seen as folk memories of distant events, more or less garbled by the passage of time: for example, it’s a common claim in the old occult literature that the story of Noah’s flood is a similar folk memory of the catastrophic global floods at the end of the Atlantean age, when the last of the great ice sheets melted and sea level shot up dozens of feet in a relatively short time.

Treat the Old Testament as the collected legends of an ancient people, the occultists suggested, and you avoid the paired traps of blind faith and blind hostility; look through the narratives rather than at them, with an eye toward other sources of evidence, and you might just glimpse dim memories of distant ages of the world.

The Fall of Humanity is one of those memories, a dim and distant echo of an event far in the past. The occult traditions also have a more detailed account of that event. Here’s the story as I was originally taught it, quite a few decades ago.

The Lemurian age was the third great cycle of human civilization on this planet; we’re currently in the fifth, and occult tradition has it that there will be seven in all. The two preceding it, the Polarian and Hyperborean ages, took place in an era when the poles were free of ice -- presumably, though this detail wasn’t discussed when I was first studying the matter, those ages happened during the last interglacial, when global temperatures were much warmer than they are today and the poles were correspondingly warmer.

By Lemurian times the poles were sheathed in ice, and a warm and fertile land mass southeast of Asia was a much better site for human societies. Over a period of many thousands of years, great civilizations rose and fell in Lemuria and in other parts of the world, most of them long since lost beneath the oceans.

(Today’s dry land, remember, was high and cold in those days, and since people in the Lemurian age apparently didn’t have cheap abundant energy sources, they left the uplands to nomadic tribes, and built their cities in warm and fertile lowland regions that are now under two to four hundred feet of sea water plus various depths of mud.)

We’re heading in the same direction.We don’t know much about the civilizations of that age, either in Lemuria or in the other parts of the world where settled communities rose. According to the narratives passed on to me, however -- for whatever that source of information is worth -- the subtle sciences of consciousness we now call “magic” were developed to a very high degree of sophistication in Lemurian times.

We’re heading in the same direction.We don’t know much about the civilizations of that age, either in Lemuria or in the other parts of the world where settled communities rose. According to the narratives passed on to me, however -- for whatever that source of information is worth -- the subtle sciences of consciousness we now call “magic” were developed to a very high degree of sophistication in Lemurian times.

At some point before the seas started rising -- nobody’s quite sure how long before that event -- that sophistication enabled Lemurian mages to make contact with certain disembodied intelligent beings who had fallen behind an earlier cycle of evolution.

There’s a fair amount of disagreement in the sources about just what these beings were and where they came from. One set of teachings proposes that they belonged to the evolutionary wave before ours -- souls, in this way of thinking, go through the process of descent into matter in waves, and many waves passed through that process long before the wave to which all human souls belong got started on its pilgrimage through material existence.

Souls in the wave before ours who flunked out, in effect, remained in contact with the material realm after their more successful peers rose up the planes to other modes of existence. Unable to take on material bodies, they were stuck here until another wave of souls -- ours -- descended to the material plane and evolved enough intelligence to interact with the stragglers of the last wave.

That’s one theory. Another claims that the beings in question are left over not from a previous wave but from what the old literature calls a previous universe and we would probably call a previous solar system.

A strange teaching found in some of the old sources claims that the planet Saturn is in some sense the remnants of a long-dead sun; in terms of our current knowledge of astrophysics, this might mean that the primal dust cloud that became the solar system received a spray of matter that had been part of a supernova, and that material ended up predominantly in the part of the cloud that became Saturn.

Did souls from that long-dead system who had failed at their evolutionary tasks drift into our solar system with that matter? It’s an intriguing thought.

These beings have a variety of names in different traditions. Those occult systems that draw on the Cabala use the Hebrew word Qlippoth, “shards” or “shells,” for the entities in question.

Those that draw more heavily on Blavatsky’s Theosophical writings prefer to call them the Lucifer spirits or Luciferian spirits.Other teachings have other names.

We can use a simpler label for them: demons. By all accounts they are conscious, disembodied beings, considerably more intelligent than we are but spiritually far more unbalanced or, if you will, debased.

Until the Lemurian age they had no access to human beings. The workings of the Lemurian mages changed that, opening a nexus by which we could contact them and they could contact us.

That nexus endures to this day, and will endure as long as our species exists. It’s a permanent part of our collective karma as a species.

Before the Lemurian age, we could ignore the demons. Now we can only overcome their influence, or fail to do so.

Since the nexus endures and works in both directions, when we overcome their influence, we complete part of our work and bring them closer to their own eventual redemption. When we submit to them, or try to control and manipulate them as the Lemurian mages did, we sink a little closer to their level, and make our own evolution as well as theirs more difficult than it would otherwise be.

The opening of the nexus of contact had another enduring effect on our species. Before that point, human beings experienced themselves as individualized parts of a whole, not as isolated, separate beings.

However dimly, they could sense the connection between their personalities (the self that endures for one life) and their individualities (the self that endures from life to life), and through the individuality, to their divine source. The workings of the Lemurian mages broke that sense of connection, and not just for themselves -- for all of us, all subsequent humanity.

It takes a lot of work to get back to where we once were.Those of my readers who’ve read mystical literature will recall the state of oneness with all things that many mystics describe, in which the self is differentiated but not separated, individualized but not cut off from the rest of creation. According to the story, that was the normal state of human consciousness before the Lemurian deviation.

It takes a lot of work to get back to where we once were.Those of my readers who’ve read mystical literature will recall the state of oneness with all things that many mystics describe, in which the self is differentiated but not separated, individualized but not cut off from the rest of creation. According to the story, that was the normal state of human consciousness before the Lemurian deviation.

That’s what we lost, and can only regain through a slow and difficult pilgrimage through the world we alienated from ourselves. That, in a very real sense, was when death entered the world -- of course material bodies died before then, but if you’re aware of your individuality and its link to its divine source, death isn’t much more of an issue than taking off your clothes before sleep, knowing that you can put on something else tomorrow.

So that’s the story as I originally learned it, and as you can find it in some occult writings -- Dion Fortune, for example, has a terse but useful commentary on the subject in her book Applied Magic. Other writers tell the story in different terms, or with different emphasis.

As I mentioned earlier in this post, classic Western occultism isn’t burdened with an orthodoxy; its narratives are meant to inspire individual inquiry, not to mummify into dogma. This is simply the version I learned first, and the one that continues to make sense to me as a way of thinking about certain aspects of the human condition.

Are any of those versions accurate accounts of something that happened more than 20 millennia ago in the subcontinent that today’s geologists call Sundaland? I have no idea.

It might be another colorful folktale, a little better suited to modern tastes, embodying an echo of ancient events.

It might be something approximating an outline of those events.

It might be a myth -- in Sallust’s useful phrase, one of those stories that never happened but always are. It might simply be a convenient metaphor that helps explain some of the features of human experience.

If it is in some sense an account of a real event, of course, it makes perfect sense that we should know so little. We know embarrassingly little about what happened a mere 5,000 years ago in the early stages of the Egyptian, Sumerian, and Indian civilizations, and far less about what happened in the late Ice Age civilizations that are all bundled up these days under the convenient label of “Atlantis.” Lemuria, or whatever its inhabitants called it back in the day, was already a matter of dim legend by the time the Atlanteans first learned to read and write.

Of all the events, achievements, and disasters of a long age, what survives to the present of Lemurian history is little more than a name, a rough sense of location, and the shadow of a tremendous mistake. It’s quite possible that when the seventh and final age of human civilization comes along, the events of our own age will be just as obscure to the people of that time as the events of Lemurian history are to us.

It wouldn’t surprise me if the legacy of our time is recalled in that far future as a name (probably not any of the ones we use now), a vague sense that human civilization in our age was in some sense centered in Eurasia, and the shadow of another tremendous mistake -- the one we made collectively when we decided that it was a good idea to try to achieve limitless economic growth on a finite planet.

“Long ago, in the industrial age…”It’s been said that people go crazy all at once in large crowds and come to their senses slowly, one at a time, in solitude. Whether or not this is universally applicable, it’s true tolerably often in human history, and I’m sure my readers can think of plenty of recent examples.

“Long ago, in the industrial age…”It’s been said that people go crazy all at once in large crowds and come to their senses slowly, one at a time, in solitude. Whether or not this is universally applicable, it’s true tolerably often in human history, and I’m sure my readers can think of plenty of recent examples.

With that in mind, I’d like to wish my readers a pleasant New Year celebration and encourage them to spend a little extra time alone over the days ahead, reflecting on how we got here and what each of us might do about it. The year about to begin promises to be a tumultuous one, and a little extra clarity may come in handy.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served 12 years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.