A Useful Kind of Madness | John Michael Greer

March 17, 2021 (EcoSophia) -- Like the last two installments in this blog’s discussion of the magical history of America -- which you can read here and here -- this post will discuss one of the factors that helped make the golden age of American occultism the astonishingly weird and creative period that it was.

The theme of this latest glance backward may not seem to have much connection with occultism, at least when compared with the secret societies and mass-market publications we explored in those earlier glimpses. Here, as so often, first impressions and commonplace notions deceive, and so a roundabout approach will be helpful.

Orville Livingston LeachLet’s start, then, with a curious book published here in Rhode Island in 1920. Its title was The White Spark and its author was one Orville Livingston Leach. Leach was a Rhode Island original of a type that has been common in this state since Roger Williams hopped off the boat. He started his career in 1879 as one of the people the city of Providence hired to go around each evening and light the gaslamps that kept city streets illuminated, and rose from that humble beginning to become, in turn, a grocery store manager, a manufacturer of patent medicines, a successful inventor in the rubber-tire industry with half a dozen patents to his name, and finally the proprietor of a spacious picnic ground south of Providence. He married, though he and his wife Theresa apparently had no children, and he was active in the Grange and the Junior Order of American Mechanics.

Orville Livingston LeachLet’s start, then, with a curious book published here in Rhode Island in 1920. Its title was The White Spark and its author was one Orville Livingston Leach. Leach was a Rhode Island original of a type that has been common in this state since Roger Williams hopped off the boat. He started his career in 1879 as one of the people the city of Providence hired to go around each evening and light the gaslamps that kept city streets illuminated, and rose from that humble beginning to become, in turn, a grocery store manager, a manufacturer of patent medicines, a successful inventor in the rubber-tire industry with half a dozen patents to his name, and finally the proprietor of a spacious picnic ground south of Providence. He married, though he and his wife Theresa apparently had no children, and he was active in the Grange and the Junior Order of American Mechanics.

All these details were simply the surface layer over the top of an inner life of splendid eccentricity. When he was not marketing medicines or inventing puncture-resistant tires for those new-fangled horseless carriages, Leach was carrying out his own idiosyncratic investigations into the nature of matter, energy, and life, and publishing the results in a series of pamphlets and two books, The Latch-Key and The White Spark. The core of his theory was that the basic unit of life was what he called “White Sparks” or “vaco-cells,” tiny bubbles of nothingness in which the luminiferous ether, the theoretical substance through which light waves move, could manifest more freely than it did in matter.

Illness, he argued, was a result of bad dietary habits that acidified the blood, making it hard for White Sparks to form; indulgence in alcohol and drugs was also an important cause. Like a good many people during the great campaign for Prohibition, he insisted that banning alcohol would cause so great an improvement in economic conditions that nobody would have to work more than four hours a day. Oh, and he also lent his support to the theory, still quite popular in some circles during his lifetime, that the Earth was hollow and the inside was habitable. He gave interviews on the subject to local papers. In 1908 he carried on a lively debate about the physics of the hollow earth; the venue was the letters column of the Providence Sunday Journal; his opponent was an earnest teenager named H.P. Lovecraft.

…and his debating partner.Leach was, in fact, a classic, bona fide, gold-plated, Grade A, 100 percent American crank, the kind of person who helped create the clichés that would eventually be exploited by all those B-movies about mad scientists in basement laboratories. Like countless other enterprising and enthusiastic men and women in this country, from long before his time to a few decads after, he was convinced that the secrets of the universe could be unraveled by a solitary researcher outside the intellectual establishment of the day, equipped with nothing more than patience, gumption, and such experimental equipment as he himself could cobble together in his spare time. It was a common belief in his time, and it gave rise to countless quests for the secrets of life, the universe, and everything.

…and his debating partner.Leach was, in fact, a classic, bona fide, gold-plated, Grade A, 100 percent American crank, the kind of person who helped create the clichés that would eventually be exploited by all those B-movies about mad scientists in basement laboratories. Like countless other enterprising and enthusiastic men and women in this country, from long before his time to a few decads after, he was convinced that the secrets of the universe could be unraveled by a solitary researcher outside the intellectual establishment of the day, equipped with nothing more than patience, gumption, and such experimental equipment as he himself could cobble together in his spare time. It was a common belief in his time, and it gave rise to countless quests for the secrets of life, the universe, and everything.

It’s become an element of our current conventional wisdom that such quests inevitably ended in failure, but that’s one of the many falsifications of history we have to deal with these days. Consider another pair of cranks who were active a little before Leach’s researches hit their stride. They were brothers who supported themselves running a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio. Like Leach, they were fascinated by one of the great scientific questions of their time, and like Leach, they became convinced that the intellectual orthodoxies of their time included serious mistakes about some of the basic principles of their subject. Like Leach, they devoted years to their own researches, and built a series of ungainly contraptions which, they insisted, would enable human beings to fly. Their names, of course, were Orville and Wilbur Wright.

1902 WrightBrosGlider. “It’ll never get off the ground,” 'they' said.The Wright brothers, please note, had no university degrees -- in fact, neither one graduated from high school -- and they carried out their epochal research into heavier-than-air flight on their own nickel. They dismissed core elements of the officially accepted aerodynamic theories of their day, having convinced themselves as a result of their experiments that the standard figures for how much lift an airfoil would generate were completely haywire. They also spent much of their time tinkering with control mechanisms, which other researchers largely ignored. They fit the standard modern definition of “crank” to a fare-thee-well. The one difficulty with this characterization was that they were right, and their device soared skyward from a North Carolina sand dune on an epochal December day in 1903. Meanwhile the flying machines created by university-trained scientists such as Samuel Pierpont Langley, who made use of the officially approved constant for lift and considered the question of control as a minor issue that could be taken care of later, racked up a string of dismal failures.

1902 WrightBrosGlider. “It’ll never get off the ground,” 'they' said.The Wright brothers, please note, had no university degrees -- in fact, neither one graduated from high school -- and they carried out their epochal research into heavier-than-air flight on their own nickel. They dismissed core elements of the officially accepted aerodynamic theories of their day, having convinced themselves as a result of their experiments that the standard figures for how much lift an airfoil would generate were completely haywire. They also spent much of their time tinkering with control mechanisms, which other researchers largely ignored. They fit the standard modern definition of “crank” to a fare-thee-well. The one difficulty with this characterization was that they were right, and their device soared skyward from a North Carolina sand dune on an epochal December day in 1903. Meanwhile the flying machines created by university-trained scientists such as Samuel Pierpont Langley, who made use of the officially approved constant for lift and considered the question of control as a minor issue that could be taken care of later, racked up a string of dismal failures.

The Wrights were hardly alone. From the time of the American Revolution until the coming of the Second World War, the vast majority of the achievements in science and engineering that took place in the United States were achieved by cranks: individual inventors pursuing their dreams in makeshift laboratories, and far more often than not basing their investigations on theories that were in flat contradiction to the officially approved scientific opinions of their time. There were thousands of them -- Wikipedia’s page on 19th century American inventors has links to 573 biographies, and those are just the famous ones -- and they played an outsized role in the immense social and economic transformations that turned the half-medieval agrarian America of 1776 into the urban industrial America of 1939.

Of course Orville Livingston Leach’s theories about the nature of life and health didn’t make any particular contribution to that process. It’s important to realize that for every inventor whose labors resulted in world-shaking consequences, there were at least a hundred others who never found whatever Holy Grail they were seeking, or who -- like Leach -- found it, or believed that they found it, and then discovered that nobody else cared. In Leach’s case, the failure of his efforts wasn’t for lack of trying; he even founded a secret society, the Order of Emorians, to spread the word of his discoveries. (Emorians? For some reason the word “Emery” appears all through Leach’s activities. His patent medicines were sold under the brand name “Doctor Emery’s.” The picnic ground he owned was Emery Park, and so on. No, nobody knows why.) But the world was full of revelations in 1920 and not enough people were interested.

The secret, of course, is that if you want a supply of Orville and Wilbur Wrights you’ve got to put up with the corresponding number of Orville Livingston Leaches. It’s impossible to know in advance which two of the crackpots laboring earnestly in basement laboratories into the small hours of the night will build a functional flying machine, and which 198 will publish pamphlets about vaco-cells, get into quarrels with budding writers of supernatural horror, and have no other discernible impact on the life of their time. All you can do, if you want steamboats and flying machines and thousands of other inventions, is encourage the cranks among you to pursue their dreams, make sure those who come up with new inventions can bring them to market, and look on good-humoredly as the others labor in vain.

Why we used to have a thriving electronics industry…That was what American society did for a very long time. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, I got to see the tail end of the culture of invention that resulted from that collective choice, in the form of books from earlier decades that were still on the shelves at public libraries. If you were a child with a taste for electronics, you could lose yourself in daydreams reading The Boy’s First (through Seventh) Book of Radio and Electronics by the redoubtable Alfred Morgan, which taught how to make the most astonishing array of radio gear from spare wire, scrap metal, oatmeal containers, and the like. Quite early on in the energy crisis of the 1970s, you could buy a book of solar energy experiments, which included such things as making a parabolic disk reflector from foil and cardboard, and building a solar oven from a cardboard box with an oven bag for glazing. Care to make your own telescope? That was a known hobby, and one that I indulged in; my first sight of the rings of Saturn through my 4” homebuilt reflector remains one of the defining memories of my childhood.

Why we used to have a thriving electronics industry…That was what American society did for a very long time. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, I got to see the tail end of the culture of invention that resulted from that collective choice, in the form of books from earlier decades that were still on the shelves at public libraries. If you were a child with a taste for electronics, you could lose yourself in daydreams reading The Boy’s First (through Seventh) Book of Radio and Electronics by the redoubtable Alfred Morgan, which taught how to make the most astonishing array of radio gear from spare wire, scrap metal, oatmeal containers, and the like. Quite early on in the energy crisis of the 1970s, you could buy a book of solar energy experiments, which included such things as making a parabolic disk reflector from foil and cardboard, and building a solar oven from a cardboard box with an oven bag for glazing. Care to make your own telescope? That was a known hobby, and one that I indulged in; my first sight of the rings of Saturn through my 4” homebuilt reflector remains one of the defining memories of my childhood.

My favorite hobby store in Burien, Washington, in those days still sold chemicals for chemistry sets, and it had an old display rack for laboratory glassware, though you couldn’t get anything fancier than a test tube by the time I started buying model rocket kits there. By “chemistry sets,” by the way, I don’t mean the timid sort of thing you see at toy stores nowadays, where you buy little packaged experiments in which the most dramatic event is that something changes color. The older kits -- hard to get in my childhood, but you could still find them if you made an effort -- avoided anything that would blow your hand off, but you could make some pretty noxious messes, which was part of the attraction for any self-respecting child. You could also learn quite a bit about basic laboratory chemistry in the process.

…among other things.Most of the sciences had some such practical application to childhood’s most pressing need, which is of course a suitable refuge from boredom. As the twig is bent, the tree’s inclined, and before my time -- when such hobbies were pervasive among intelligent teenagers across the country -- the result was a thriving amateur science scene in just about any field you care to name, which not uncommonly overturned the applecart of the official sciences. The White Spark was a product of that same culture of independent invention and discovery; it veered off in its own idiosyncratic direction, to be sure, but it was far from the strangest quest that unfolded from the same cultural pressure that put the Wright brothers into the history books.

…among other things.Most of the sciences had some such practical application to childhood’s most pressing need, which is of course a suitable refuge from boredom. As the twig is bent, the tree’s inclined, and before my time -- when such hobbies were pervasive among intelligent teenagers across the country -- the result was a thriving amateur science scene in just about any field you care to name, which not uncommonly overturned the applecart of the official sciences. The White Spark was a product of that same culture of independent invention and discovery; it veered off in its own idiosyncratic direction, to be sure, but it was far from the strangest quest that unfolded from the same cultural pressure that put the Wright brothers into the history books.

Consider Cyrus Teed, a contemporary of Leach’s who picked up the hollow-earth theory and carried it that one step further into the absolute elsewhere. Teed became convinced, as a result of a visionary encounter with the great mother goddess of the cosmos, that the world is hollow and we live on the inside. On the basis of this revelation and a great deal more, he gathered together a substantial following, took the name Koresh (the Hebrew version of his first name), founded an organization called the Koreshan Unity, and established a planned world capital of the future in southern Florida. (It’s still there, 20 miles south of Fort Myers, though it’s a state campground now.) He and his followers carried out scientific experiments with a gigantic spirit level, which appeared to show that the curvature of the Earth’s surface was concave rather than convex. When he died, his followers waited three days before proceeding with the funeral, to give him a proper chance to rise from the dead.

Koresh Teed. Last I checked, he’s still dead.By now my more impatient readers will be wondering what all this has to do with the history of American magic. It’s quite simple, really. Occultism is never really separate from the society in which it occurs. It’s no accident, for example, that grimoires written in the Middle Ages present what amounts to a feudal theory of magic, in which the mage does homage to God and receives from his divine suzerain the right to lord it over a peasantry of demons and spirits. Nor is it an accident that the mages of the Renaissance were just as fascinated by the prospect of reviving the high traditions of a vanished past as their humanist opposite numbers -- they just wanted to revive different high traditions from a very differently conceived past. In exactly the same way, when the Theosophical Society brought the occult traditions of east and west to the attention of millions of Americans who were used to the idea of earnest inventors in basement laboratories overturning the ideas of the status quo, they applied that same idea to occultism, and thousands of them got to work trying to discover the occult secrets of the ages in exactly the same spirit that the Wright brothers applied to flight and Orville Livingston Leach applied to the White Spark.

Koresh Teed. Last I checked, he’s still dead.By now my more impatient readers will be wondering what all this has to do with the history of American magic. It’s quite simple, really. Occultism is never really separate from the society in which it occurs. It’s no accident, for example, that grimoires written in the Middle Ages present what amounts to a feudal theory of magic, in which the mage does homage to God and receives from his divine suzerain the right to lord it over a peasantry of demons and spirits. Nor is it an accident that the mages of the Renaissance were just as fascinated by the prospect of reviving the high traditions of a vanished past as their humanist opposite numbers -- they just wanted to revive different high traditions from a very differently conceived past. In exactly the same way, when the Theosophical Society brought the occult traditions of east and west to the attention of millions of Americans who were used to the idea of earnest inventors in basement laboratories overturning the ideas of the status quo, they applied that same idea to occultism, and thousands of them got to work trying to discover the occult secrets of the ages in exactly the same spirit that the Wright brothers applied to flight and Orville Livingston Leach applied to the White Spark.

In fact, all three of the trends we’ve tracked in recent months helped drive the golden age of American occultism in much the same way. When that era began, the giddy assortment of philosophers, visionaries, wizards, diviners, occult entrepreneurs, and bona fide crackpots who set it in motion found themselves blessed with three extraordinary advantages. The first was the lodge system, a familiar, functional, and highly adaptable system for founding and running voluntary organizations; the second was a large and lucrative publishing industry eager for new writing on occult subjects, together with a reading public just as eager to snap up the volumes that resulted; and the third, perhaps the most important of all, was a widespread enthusiasm on the part of the American people for hard solitary work in pursuit of eccentric goals.

All three of these things could easily be put to work by occultists for their own purposes, and as we’ll see, all three of them were. The result was one of the most extraordinary eras of occult creativity in recorded history.

After that era ended, in turn, two of those three things went away. Occult publishing remains a booming business to this day, of course -- a detail of history to which I owe a great deal, starting with the fact that I quit my last day job in 1996 -- but the other two factors did not survive. We’ve already discussed the systematic erasure of the fraternal lodge system from American society and history. The erasure of the culture of innovation and individual research discussed in this week’s post took longer, but it was carried out with just as much thoroughness.

How too many American libraries treat their books these days.I mentioned above that I got to see some of the tail end of that culture in my insufficiently misspent youth. Even then, though, I knew very few other kids who were interested in such things, and getting access to the necessary information became increasingly difficult as the 20th century waned. If my experience is anything to go by, certainly, how-to books about science and technology of the robust sort just discussed were among the things that vanished first once American public libraries took up the Orwellian habit of purging “unsuitable” books from their collections. Meanwhile the kind of open-ended chemistry sets and engineering-themed toys I grew up with were replaced by what, back then, I called “dead end kits” -- the kind of rigidly limited set of parts or ingredients that’s set up to let you do one and only one thing.

How too many American libraries treat their books these days.I mentioned above that I got to see some of the tail end of that culture in my insufficiently misspent youth. Even then, though, I knew very few other kids who were interested in such things, and getting access to the necessary information became increasingly difficult as the 20th century waned. If my experience is anything to go by, certainly, how-to books about science and technology of the robust sort just discussed were among the things that vanished first once American public libraries took up the Orwellian habit of purging “unsuitable” books from their collections. Meanwhile the kind of open-ended chemistry sets and engineering-themed toys I grew up with were replaced by what, back then, I called “dead end kits” -- the kind of rigidly limited set of parts or ingredients that’s set up to let you do one and only one thing.

That wasn’t accidental. In the aftermath of the Second World War, scientific discovery stopped being something that individuals did in their basement laboratories, and became something that officially qualified, university-trained experts did in expensive laboratory settings tightly controlled by the iron triangle of government, corporate, and university bureaucracies. Professional scientists stopped taking independent researchers seriously and started making snide comments about “citizen scientists” instead. The war carried on by the medical-industrial complex against alternative health care is simply one of the most visible expressions of the change that resulted. What defines something as “alternative health care?” The one consistent factor -- and by “consistent” I mean there’s a 1.00 correlation -- is that officially approved mainstream medicine makes profits for big corporations, while alternative medicine does not.

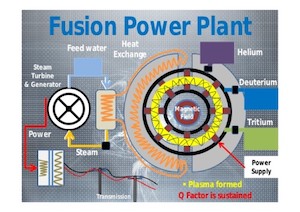

One of the downsides of that shift, of course, is that today’s equivalents of the Wright brothers, even if they go against all the pressures arrayed against them and invent something, won’t be able to get a hearing for their creation, unless it’s within one of the narrow range of approved fields where individual innovation can easily be coopted by corporate interests. That means that in a significant and growing number of cases we’re stuck with the equivalent of Samuel Pierpont Langley’s failed airplane tests, repeated endlessly with ever larger budgets. Look at the history of fusion power, to cite only the most blatant example, and that’s what you’ll see: a failed model endlessly rehashed, because too many influential scientists have too much of their reputation committed to that model, and the penalties for failure are minimal while the career rewards of trudging along the same rut are substantial.

When I was born in 1962, this was just 20 years in the future. It still is.If fusion power is ever going to become a reality, it won’t be gargantuan government-funded projects rehashing the failed Tokamak model of magnetic confinement that do it. It’ll be some other approach that nobody in the fusion-research bureaucracies has thought of, something as off the wall as the Wright brothers’ rejection of the established constant for airfoil lift and their seemingly irrelevant focus on control mechanisms. The best way to achieve the sort of breakthrough the Wrights accomplished is to make sure you have many different people working in many different directions, following their own passions, free from the kind of bureaucratic oversight that insists on toeing the line of the accepted scholarly consensus -- and the best way to make that happen, in turn, is to encourage individual initiative in science and engineering by lowering the barriers and prejudices against citizen scientists and basement inventors.

When I was born in 1962, this was just 20 years in the future. It still is.If fusion power is ever going to become a reality, it won’t be gargantuan government-funded projects rehashing the failed Tokamak model of magnetic confinement that do it. It’ll be some other approach that nobody in the fusion-research bureaucracies has thought of, something as off the wall as the Wright brothers’ rejection of the established constant for airfoil lift and their seemingly irrelevant focus on control mechanisms. The best way to achieve the sort of breakthrough the Wrights accomplished is to make sure you have many different people working in many different directions, following their own passions, free from the kind of bureaucratic oversight that insists on toeing the line of the accepted scholarly consensus -- and the best way to make that happen, in turn, is to encourage individual initiative in science and engineering by lowering the barriers and prejudices against citizen scientists and basement inventors.

Whether that’s going to happen in time to make any kind of difference in the near term is an open question. I’d like, however, to encourage any of my readers who have an interest in some form of research or invention to consider pursuing it, whether or not it belongs to those branches of science or invention that are considered respectable by the white-coated bureaucrats who too often pass for scientists these days. I’d also like to encourage any of my readers who have friends or family members who take up some such hobby to be as supportive as possible, and consider taking an interest in the work. If your friend or spouse or teenage child seems to be turning into a mad scientist, remember that this can be a useful kind of madness. Even if you don’t end up watching your friend or spouse or teenage child soaring through the sky on a flying machine, you might get a puncture-resistant tire or a conversation with a budding horror writer out of the spark of individual inspiration the world needs very badly just now.

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served 12 years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He now lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.

- CreatedSunday, March 21, 2021

- Last modifiedSunday, March 21, 2021

World Desk Activities

www.niemanlab.org/2024/04/inside-newsweek-ai-exper…

www.journalismfestival.com/programme/2024/reader-r…

Reader revenue beyond the English language – – International Journalism Festival

In the past few months, many news publishers in the US have announced layoffs. Others have tweaked or abandoned their paywalls and pursued more open models.…

phys.org/news/2024-04-surf-clams-coast-virginia-re…

Surf clams off the coast of Virginia reappear and rebound

The Atlantic surf clam, an economically valuable species that is the main ingredient in clam chowder and fried clam strips, has returned to Virginia waters…

medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-antibiotics-reveal-…

Antibiotics reveal a new way to fight cancer

Cancer cells grow and spread by hiding from the body's immune system. Immunotherapy allows the immune system to find and attack hidden cancer cells, helping…

phys.org/news/2024-04-crucial-quantum-internet.htm…

Crucial connection for 'quantum internet' made for the first time

Researchers have produced, stored, and retrieved quantum information for the first time, a critical step in quantum networking.

medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-women-major-complic…

Women who experience major complications during pregnancy found to have increased risk of early death years later

A team of medical researchers from the University of Texas Health Science Center, in the U.S., and Lund University, in Sweden, has found via study…

medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-common-hiv-treatmen…

Common HIV treatments may aid Alzheimer's disease patients

Alzheimer's disease (AD) currently afflicts nearly seven million people in the U.S. With this number expected to grow to nearly 13 million by 2050, the…

medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-adolescent-stress-p…

Study suggests adolescent stress may raise risk of postpartum depression in adults

In a new study, a Johns Hopkins Medicine-led research team reports that social stress during adolescence in female mice later results in prolonged elevation of…

Latest Stories

Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Speaking Freely: Obioma Okonkwo April 23, 2024

- Screen Printing 101: EFF's Spring Speakeasy at Babylon Burning April 23, 2024

- Podcast Episode: Right to Repair Catches the Car April 23, 2024

- U.S. Senate and Biden Administration Shamefully Renew and Expand FISA Section 702, Ushering in a Two Year Expansion of Unconstitutional Mass Surveillance April 22, 2024

The Intercept

- “Little Home Market”: The Connecticut Company Accused of Fueling an Execution Spree April 25, 2024

- House Responds to Israeli-Iranian Missile Exchange by Taking Rights Away from Americans April 25, 2024

- U.S.-Trained Burkina Faso Military Executed 220 Civilians April 25, 2024

- “Kill All Arabs”: The Feds Are Investigating UMass Amherst for Anti-Palestinian Bias April 24, 2024

VTDigger

- Final Reading: New USDA program aims to help towns access federal disaster relief April 25, 2024

- Vermont’s new fair and impartial policing policy aims to reduce bias based on citizenship April 25, 2024

- Mike Pieciak announces reelection bid for Vermont state treasurer April 25, 2024

- Senate’s version of budget would reduce motel program room capacity by a third April 25, 2024

Mountain Times -- Central Vermont

- Mountain Times -Volume 52, Number 17, April 24-20, 2024 April 24, 2024

- Weekly Horoscope — April 24-30, 2024 April 24, 2024

- Loon vs. Canada goose: A battle for Goose Poop Island April 24, 2024

- A break in the action April 24, 2024